I had an up-and-back errand to NYC yesterday. Much of my time was spent waiting, and I was parked for a while behind this thing. Which I soon noticed was a curiosity for passing tourists. Statue of Liberty > Cybertruck > Empire State Building. No one mocked it, which I admit surprised me. They were fascinated. The Europeans seemed especially into it, go figure. So to pass the time I pretended I was interested too but took photos of them for the human-behavior file.

A New Cabal

So we’re ruled by actual demons.

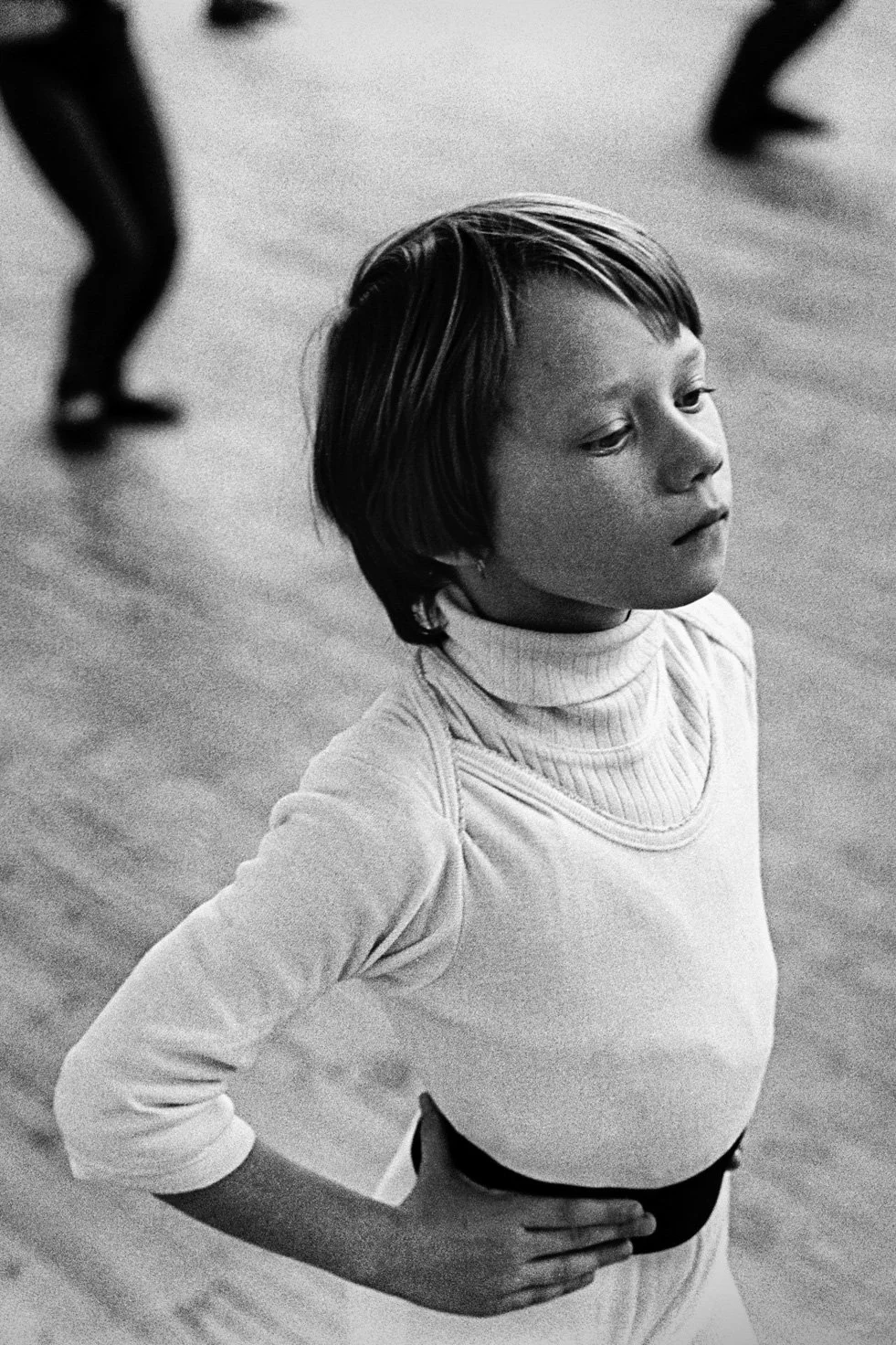

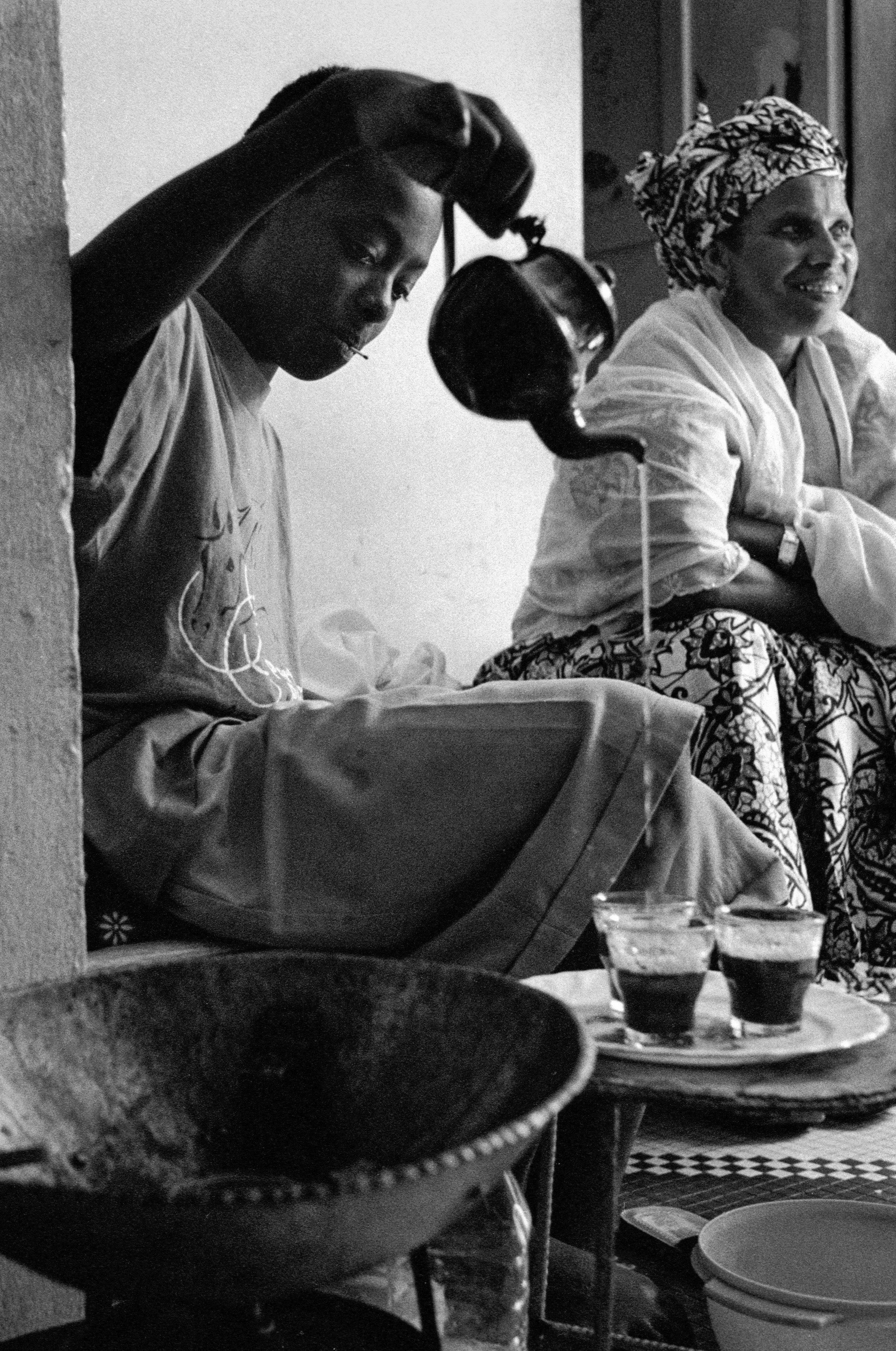

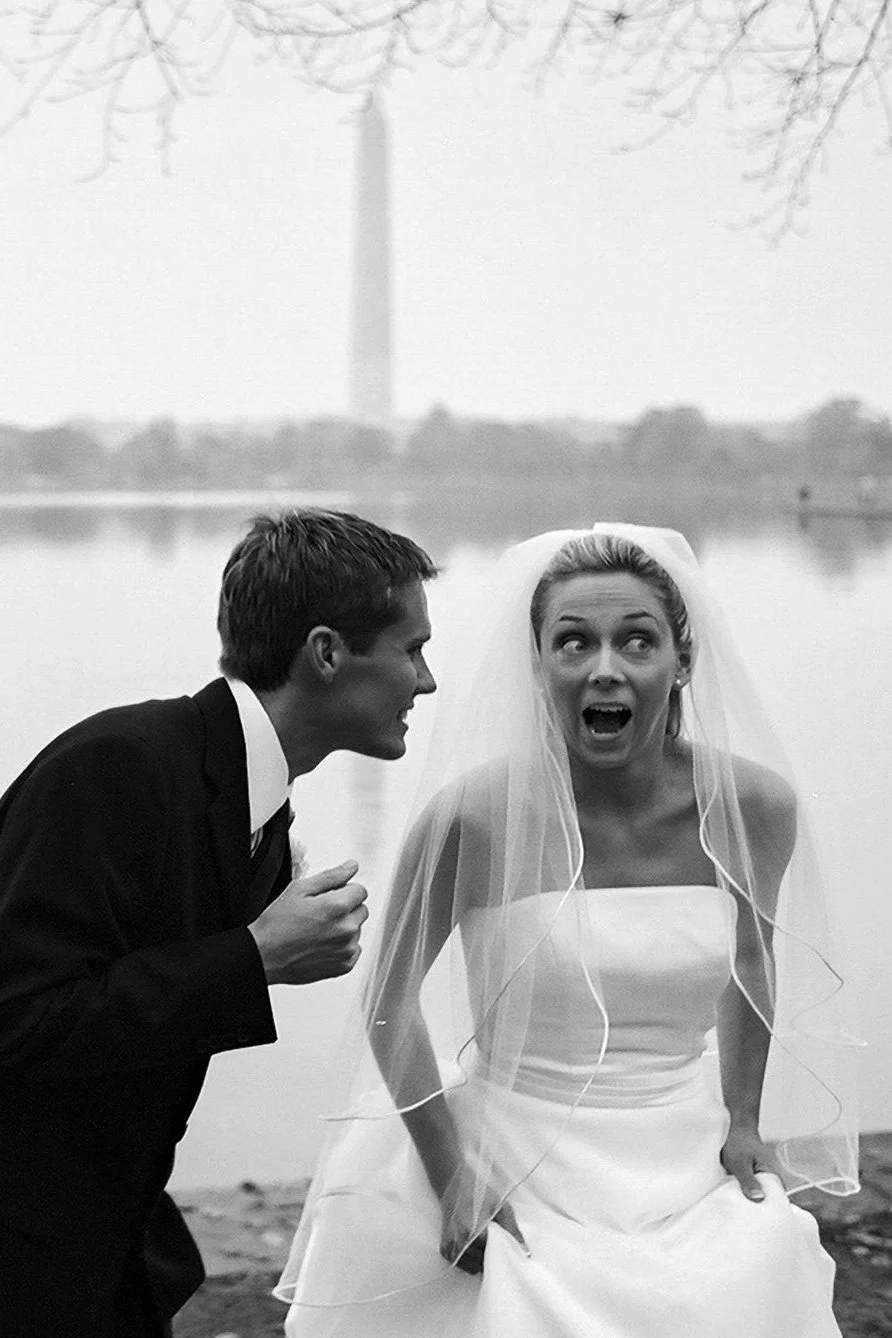

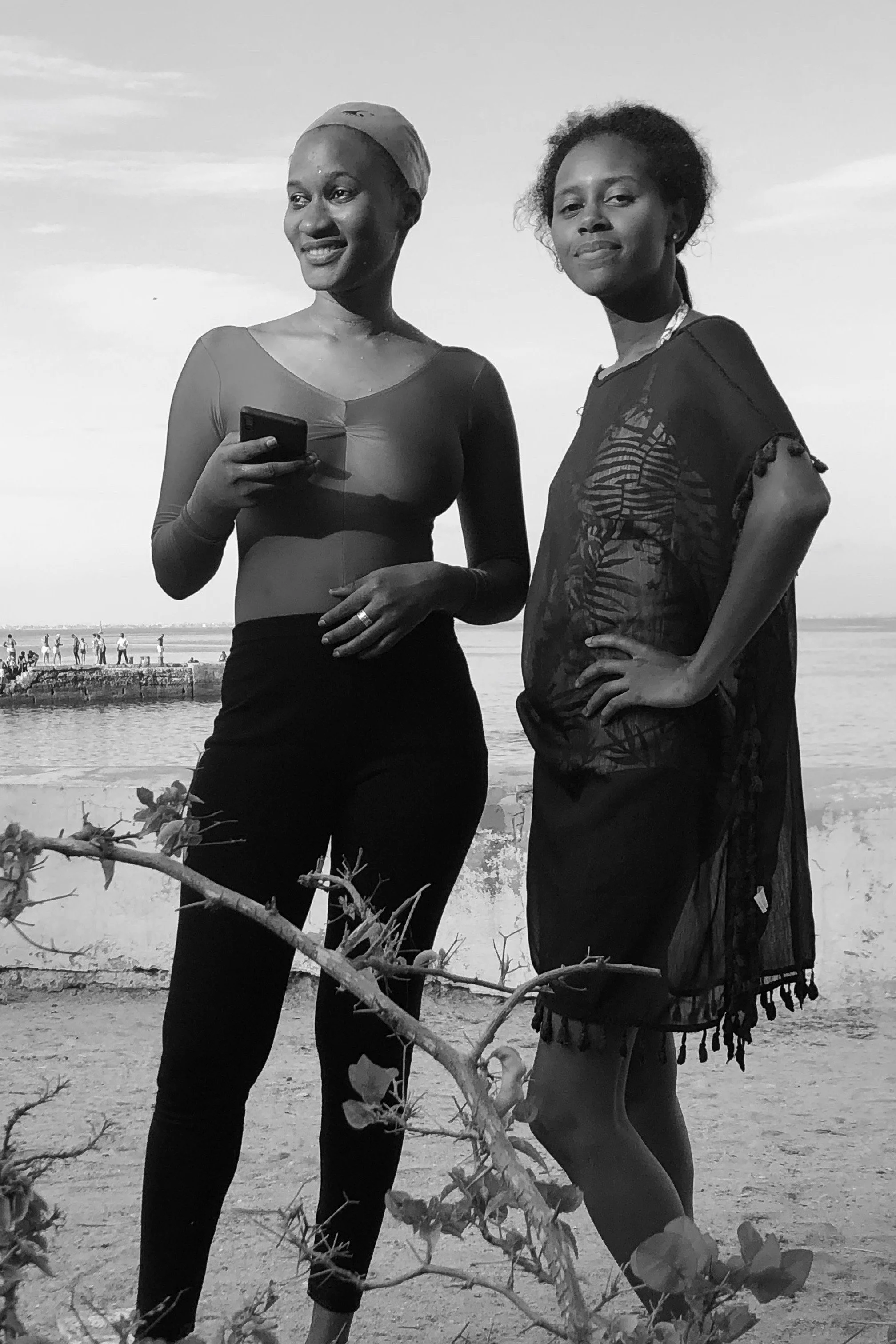

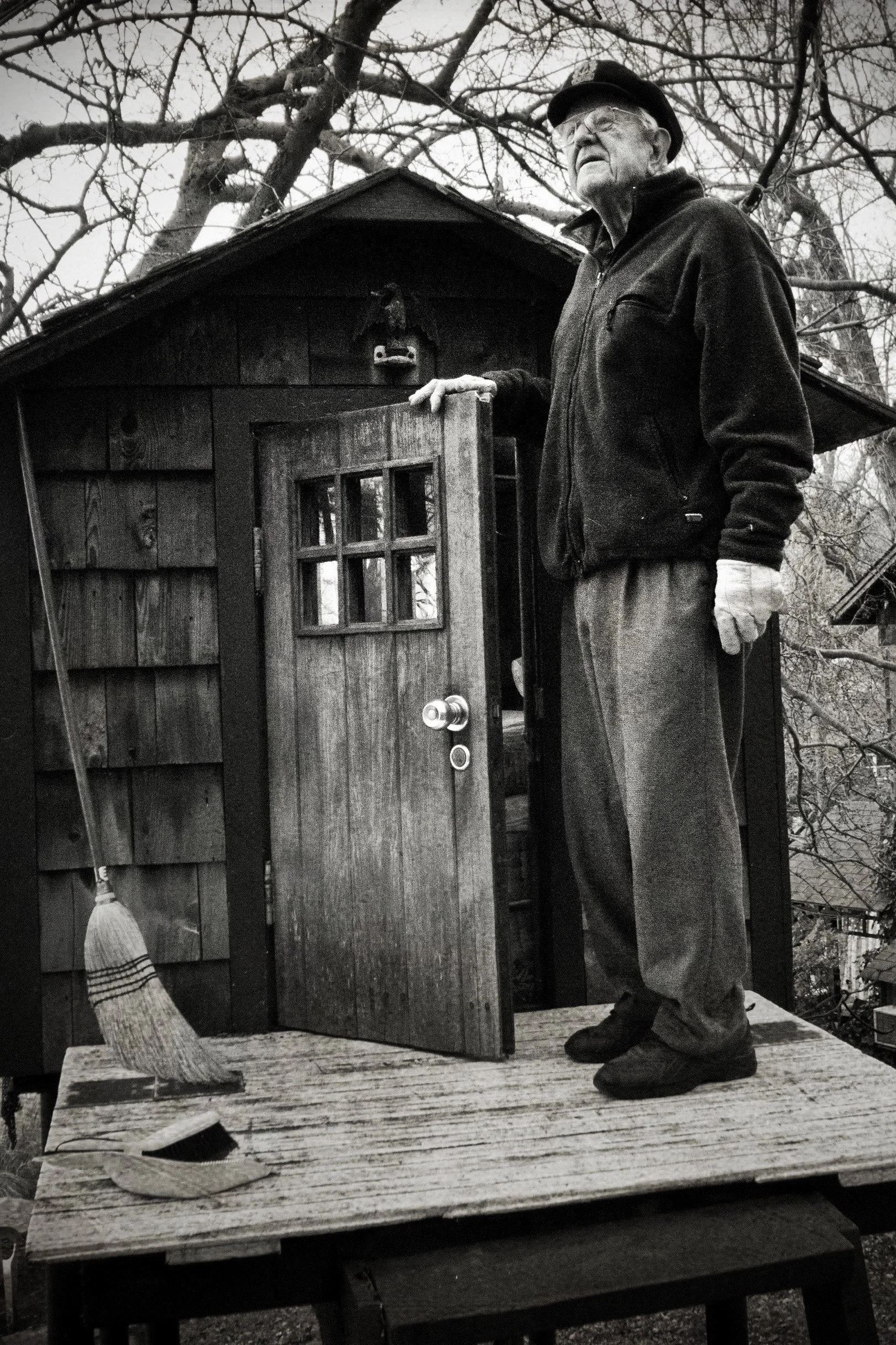

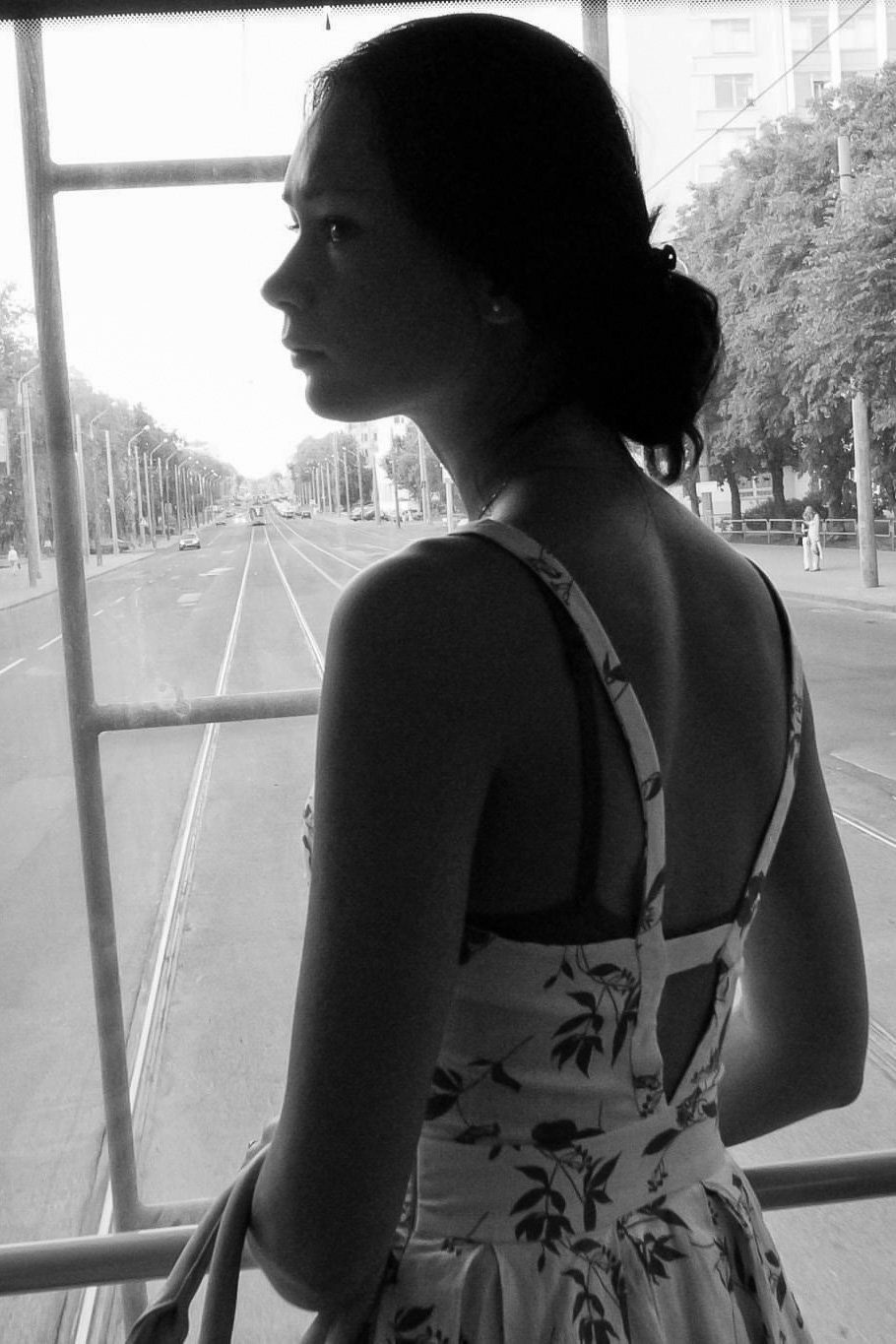

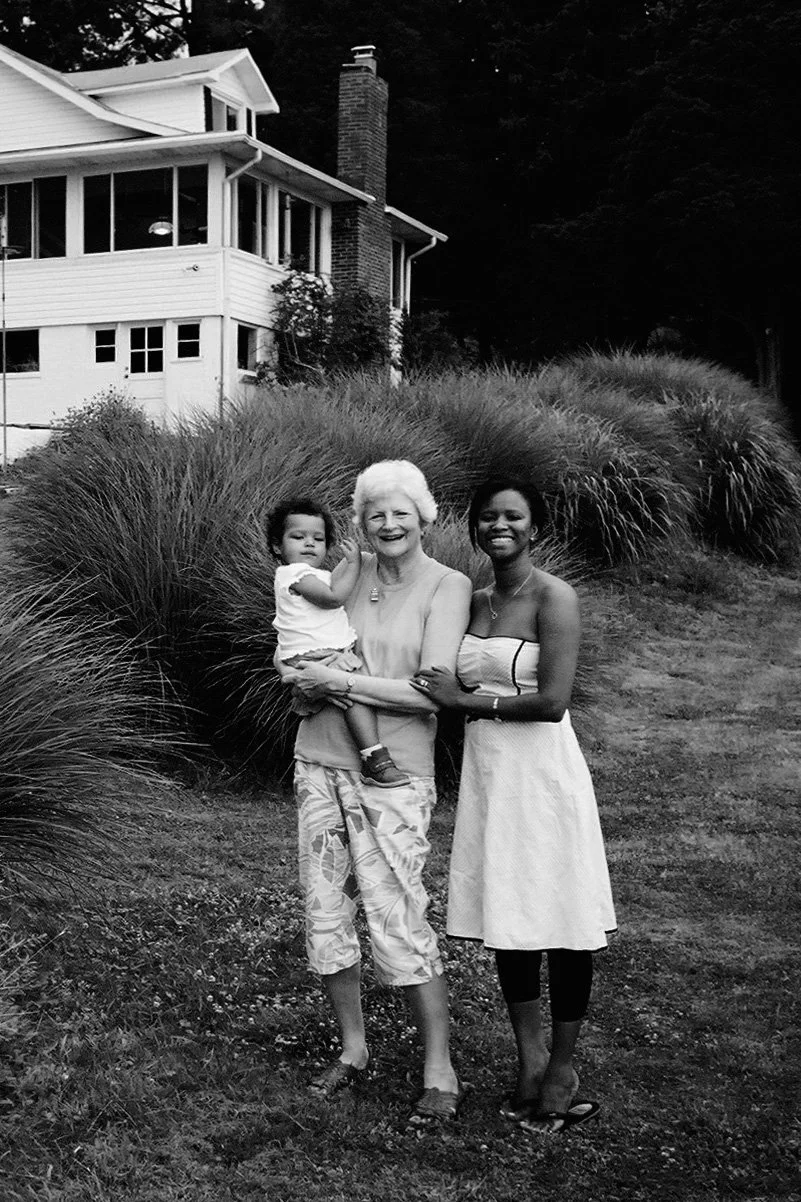

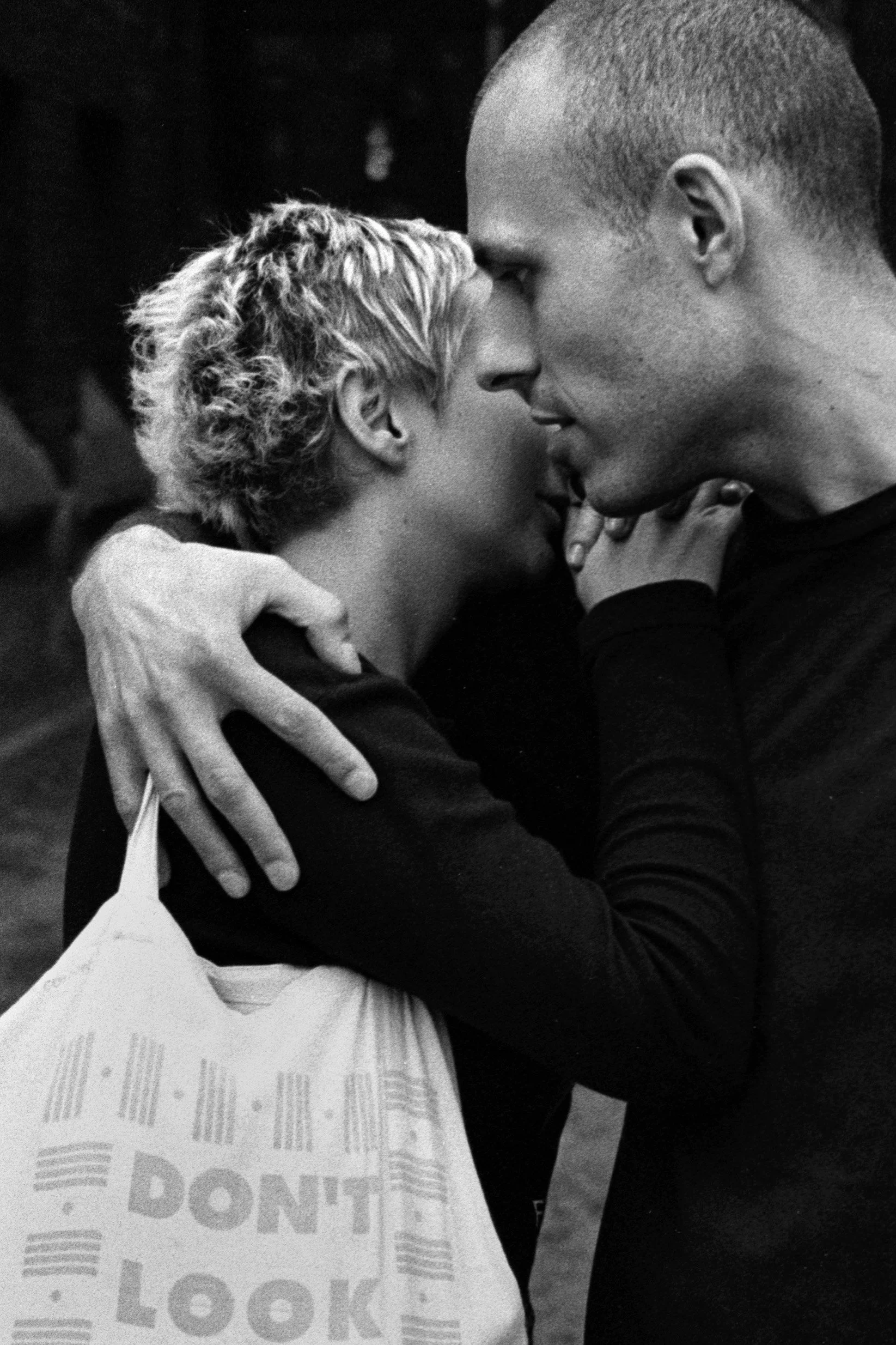

I was preparing a long-winded, somewhat grandiose response but I ditched that. Instead I’ll just offer a set of photos as a rebuttal, a kind of yearbook collection of my own ‘cabal’.

Not the club of gremlins in the shadows, bound by complicity and depravity. Those of us who live in the light, who show up for each other, create beauty and life no matter the time or place or circumstance.

We shape the world, not you m-f’ers.

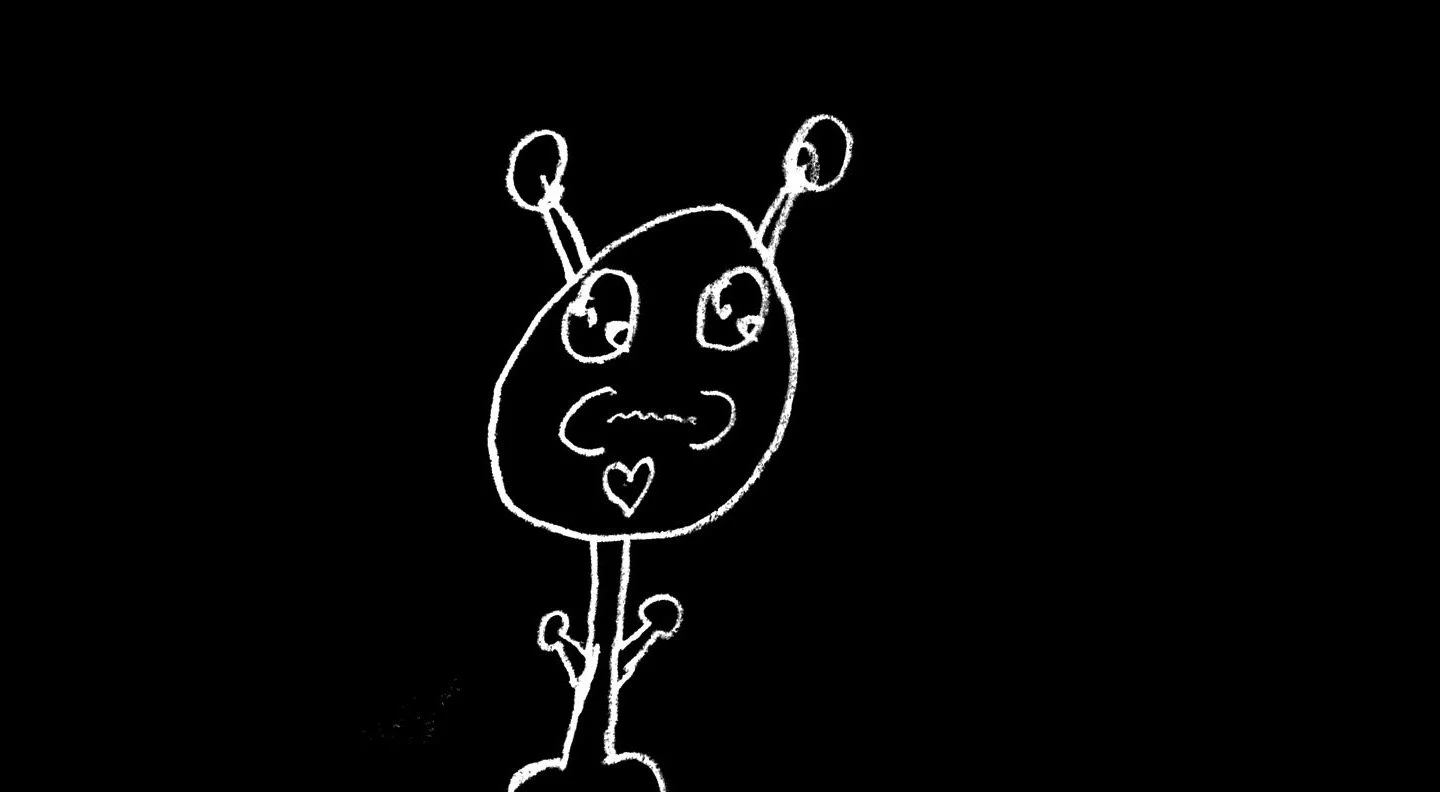

Drawing by Sofia for New World Voyage album art

On Future-Music

What is future music, what do you mean, Bill?

Put simply, to me it’s music that carries us forward and helps us imagine a better future. Stories and ideas that look ahead more than back.

Music that doesn’t get trapped in the amber of various genres. I think genres are actually the enemy of future-music. Not because everything needs to be wildly experimental but overly revering any genre risks making it a kind of museum piece that you are simply mimicking.

I think the trick is to keep building on what has come before. My favorite music does that. I remember the first time hearing Sigur Ros, it was like they invented a new musical vocabulary where I didn’t always know where it was going but still felt richly rewarding. It evoked whole new landscapes in my mind.

Of course, future music will be different for everyone, music is so personal. Right now your inner voice might be piping up with the kinds of music you like. But it’s not so much about that per se, or music as comfort-food entertainment. Getting at the notion of future-music means learning to think about music differently. Being receptive to an artist’s vision and how it can crack you open to new possibilities, sort of like a good book does. Or photography, it totally ties in with how I teach photo ‘authorship’ based on personal vision.

These days we have the devaluation of music, creeping AI, and the general trend of music becoming simply a formulaic commodity. Too often artistry gets lost or overlooked.

So how can we expect music to carry us forward anymore? Who’s even doing it, what would that look like?

I had a great time exploring these questions on Thursday night, co-hosting a two-hour Takoma Radio show with the ‘Night Nurse’, Madona Tyler LeBlanc, and I performed a couple songs live in the studio at the end.

You can find it in the archives here if you’re so inclined. I’ll do a quick recap here while it’s fresh.

First we played and discussed samples from my own playlist, songs that feel like the future to me. Search ‘em up wherever you do music.

Dawning - Yasmin Williams

Yasmin is one of the most innovative and talented guitarists out there, a rising star (and she’s from the DC area!). In this track that virtuosity is put in service of a lovely spring-in-bloom sonic landscape. While she plays the likes of Newport Folk Festival, I would say she’s Exhibit A of future-folk, looking forward not backward.

Little Odessa - Eric Hilton (feat. The Infinite Daisy Chains)

Another DC stalwart, Eric is one of the co-founders of Thievery Corporation, who helped pioneer the lounge/electronica genre in the late 90s. So creating a new genre certainly puts you in the future-music category. But even within their electronica there was world-building going on, a cinematic international stew. As a solo artist Eric has been equally prolific. This track is just one example of his continued formidable vibe-conjuring prowess, this time in collab with fellow DMV-ers The Infinite Daisy Chains, who clearly can hold their own in the future-vibe department.

The Great Big Warehouse in the Sky - Petur Ben

Petur Ben, a fixture in the Reykjavik indie music scene, on one hand is just a guy with an acoustic guitar. But his finger-picking style is dynamic and unusual, as is his voice and songwriting. This song springs from his time in Ukraine, a poetic anthem of sorts for Ukrainian youth he met who use their underground club culture as a sanctuary from decades of crisis after crisis that cloud their future. It’s a good example of how a song can be topical yet not didactic or preachy.

Habibi (A Clear Black Line) - Loney Dear

Loney Dear is a Swedish singer-songwriter named Emil Svanängen, often dubbed Sweden’s Brian Wilson. In contrast with his more layered arrangements, this track is minimalistic, totally stripped down to his voice and piano. Voice bone-dry, no reverb, almost painfully intimate. Feels like a live take in a living room, which likely what it is. What really sets it apart is that it’s a song for immigrants, a plaintive call for more mercy and decency in how we welcome them. It’s a protest-song-as-lullaby, taking us forward by showing us how to get a point across and engage people in new ways.

There Are Several Alberts Here - Loney Dear

I including this one too as an example of his fuller arrangements. It leads off with random steampunk bleeps and blurbs. As it continues, with low chords swelling and mysterious reverb-drenched cracks and snaps in the distance, what emerges with the melody and chords is more like a power pop song in disguise, buried in the fog. Melancholic but quite catchy and astonishingly inventive.

Others that we didn’t get to but you might want to check out:

Fighter - ISAK (“women on the move, we fight for each other”)

Like Real People Do - Hozier (nature version)

Open the Light - Boards of Canada (the sonic equivalent of waking up in the future with a mix of hope and disorientation)

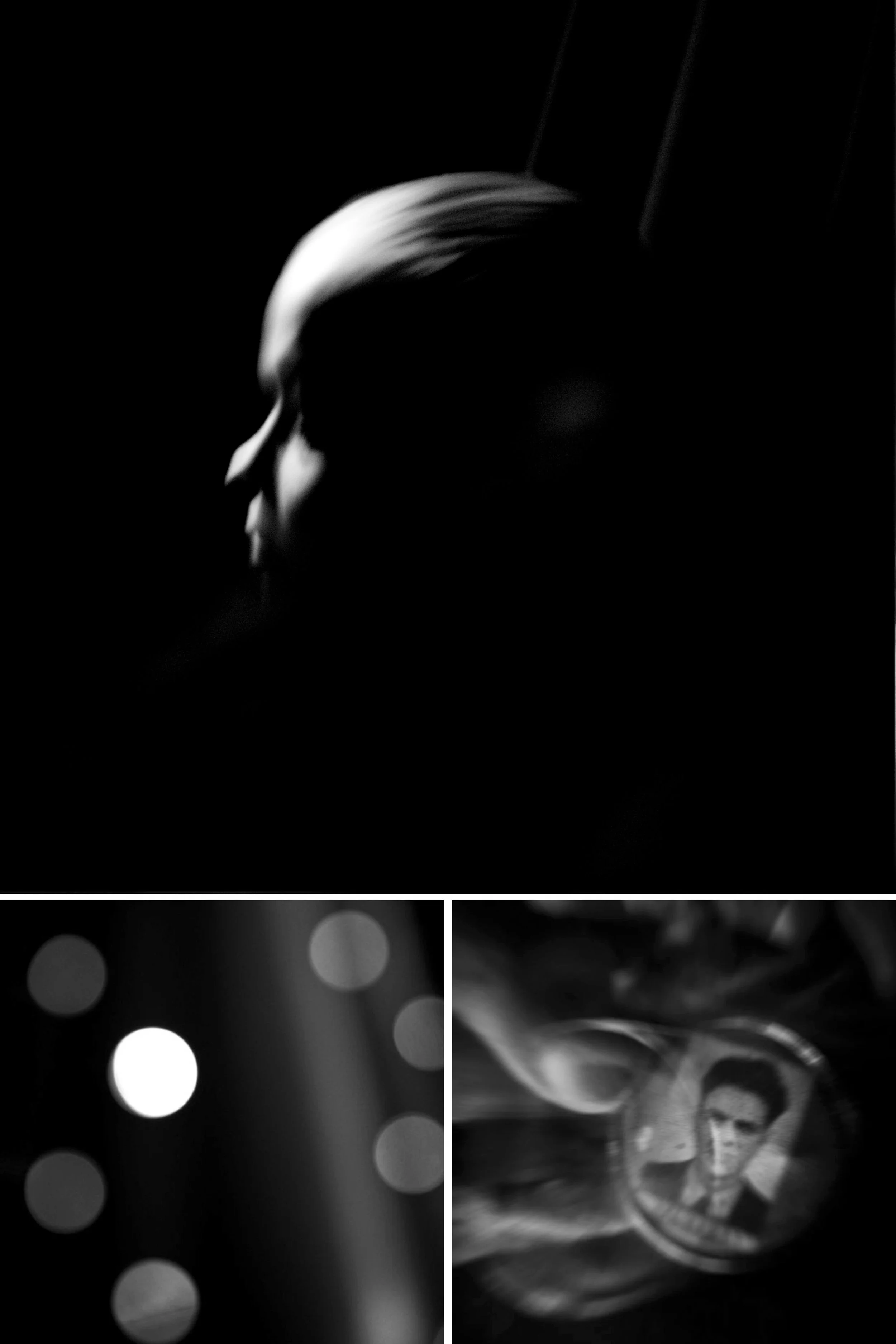

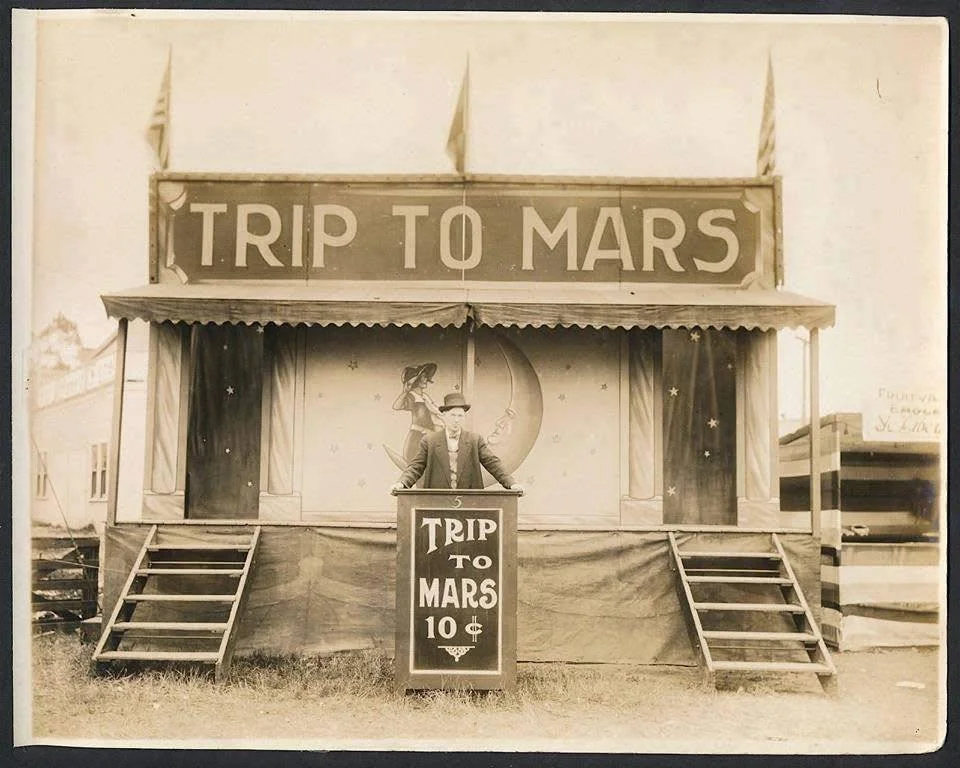

In the second hour we discussed my 2016 concept album New World Voyage, which I’m super proud of, as an example of future music of my own. In this case it’s literally *about* the future, the first humans to leave Earth forever for Mars. The sequence of tracks and album art suggests a loose story about what happens to them.

Images from the New World Voyage digital booklet

I generally think of my songs as future-folk, in this case the songs of the journey itself from the perspective of the crew. We played three tracks - Love Again, Echoes, and Feel - and talked about their roles in the narrative.

We ran short on time but I played two songs live. Feel, to show how I rearranged it for solo acoustic. And Heavenly, a song I wrote years ago in a band I was in but now fits well in my Mars suite.

The joke is that the world went to shit when David Bowie died, but there’s some truth to it. He was a good example of someone always pointing the way forward, toward something better, in interesting and humanistic ways. I don’t think we have enough of that now, and we’re hurting as a result.

More future-music might at least help us believe in the future again.

The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night

Shelter from the Storm

“What does courage look like inside systems that punish it?”

I was forwarded that question from someone who was developing a film series on resilience in fascist times. What a great prompt.

I had been thinking recently about the films I used to show my former photo students and how they could be useful now. Those were the before-times but in addition to the aspects I was hoping to convey to them in photo class - empathy, critical thinking, careful attention, eye for composition, and understanding unconventional narrative structures - I see how some of those films could offer answers to the question above. Or at least good followup questions.

Such films challenge the viewer. They are certainly not necessarily happy-happy or even obviously hopeful to the casual viewer. A few are even quite dark. But none are banal, none are formulaic, each is enriching and ultimately hopeful. Or if not hopeful at least grounded in real humanity and to me that counts for a lot. Some center on the power of art, music, beauty, nature, knowledge, or simply the act of maintaining courage in the face of fear and hopeless times.

I’ll give you a recent example to set this up a bit more. I went to see the new 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple the other day. I’ve followed the whole franchise and I’d heard good things about this one, even compared to its predecessor last year. (By the way, on the way there I noticed a small sign for a doctor’s office, a Dr. Kelson, who, if you don’t know, figures prominently in the film. What are the odds?)

I sat through the previews, which were the usual fare - depressing, brainless reminders of how assembly-line so many movies are these days. When you see the prevalence of violence, nihilism, anti-humanism (also overly sugar-coated kitsch, a kind of fake humanism), gender stereotypes, etc, plus the utter lack of critical thinking they require, it starts to make more sense where we find ourselves these days.

Anyway, then came the main attraction. Ok, yes, it’s quite brutally violent early on. I mean Bone Temple IS a zombie horror film. But soon it made me understand it was necessary to first be nauseated by the violence in order to counteract it. And in this film the worst violence is by broken people, not the infected.

Without giving anything away, I would argue the film gradually and subtly reinforces humanism for the viewer on several levels. Even the humanity of some villains and zombies themselves. I can’t describe the ending itself without spoiling it, but its unexpected poignance took my breath for a minute. There’s also a clever throwaway line about fascism and examples of empathy near the end which will surely be decried as woke. Lord help us.

The point is: what we watch matters, it shapes our outlook. It matters that we watch critically and carefully for what a good film can offer, and that hope and humanity can arrive in surprising forms if we’re open to it. Amid the gore and apocalyptic setting, Bone Temple offers more human values in its own way than any Disney film.

I left feeling a bit changed, always a good sign.

Which brings me to a short list of films I’m going to recommend in that spirit. I’m planning in-person community viewing and discussion events for these films, so if you’re local stay tuned. Or maybe we can add an online component, I’ll work on that. I’m not going to embed trailers here, for one thing they don’t work well in this newsletter format, but I will link the titles. You’ll have to look around to see where to stream them. Most of these I own and have watched many times.

All are ultimately about beauty and courage. In our systems that increasingly punish both.

If you’ve never seen it, it’s time. Joyful, electric, exuberant, funny, and of course great music in what was a somewhat dismal period in early 60s post-war England (ok, as opposed to the dismal 70s-80s Thatcher years, or the faux-sunniness of Tony Blair’s ‘Cool Brittania’, or Boris Johnson’s hair, or the ten minutes Liz Truss was in there, BUT I DIGRESS). It’s actually a quite avant-garde piece of filmmaking, more in line with the French new wave of the time. Punctures the burgeoning world of marketing to teenagers in an iconic, absurdist scene with George Harrison and an ad exec (with lines like “The new thing is to care passionately and be right-wing”). Takes aim at authority, inertia, and class throughout, and shows how to create a more exciting reality amid stasis. It’s four guys that made virtually everyone feel differently about the world. THAT ENERGY.

A short, gorgeously-animated film that is not really for kids (though I’d say suitable for any age 7+). Centered on the making of the first illustrated bible, the real-life Book of Kells, in a fortified village in medieval Ireland during a period of rampant Viking raids, it’s really about the power of art and beauty in existential times. Even when - especially when - you’re losing. It weaves in a lot of historical layers, especially around the tension between paganism and the newer arrival of Christianity. Truly incredible visuals in service of brisk storytelling. Spoiler: the battle is indeed lost but beauty and humanity still win the war.

A profound documentary, by director Wim Wenders, on the late Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado. After a lifetime covering tragedy and suffering on a global scale, Salgado is worn down, sick. He turns to making images of nature’s power, and he and his wife retreat to his family farm where they oversee an astonishing revitalization of land ravaged by climate change. A stunning example of how individuals can make a difference. Salgado himself is a deep, enigmatic, monk-like presence, and his photography and Wenders’ sensitive vision are top-notch.

A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks

Finally, the first excellent documentary about one of the greatest, larger-than-life photo warriors of modern times. A big element of the film’s power is the historical sweep from the civil rights era to the modern day and its focus on the younger generation of African-American photographers taking their inspiration from Parks. And it shows what an incredible renaissance man he was. (Yeah, it’s HBO, but it’s also on Amazon and Kanopy.)

This one might seem an odd choice for a list of hope-films. While maybe the most accessible work by the late Hungarian auteur Bela Tarr (compared to, say, his seven-hour Satantango), WH is not for the faint of heart. A desolate town falls into madness with the ominous arrival of a ranting but unseen demagogue and a strange ‘circus’ comprised of a single attraction: a giant stuffed whale in a trailer truck. Brooding MAGA-types gather in the town square, and eventually explode in mindless violence that culminates in one of the most astonishing sequences in cinema. The main character is a kind of ‘holy fool’, both simple and seemingly the only one with both sanity and compassion. The film is also not for the short attention-ed, it takes its time letting things unfold. Tarr is famous for extremely long, uncut shots, a refusal to offer traditional comforts to the viewer, and heavy themes. He’s in his gear and you have to get there too. But the imagery is astonishingly beautiful, if bleak, and a few moments are even darkly funny (especially the opening scene). If you’ve got the stomach to hang in there, it will pull you in and work its spell, even if you don’t quite know what to make of it all. Things don’t end well but even in that there is a certain empathy to be found.

And Tarr pushed the boundaries of cinema like no other. Two and a half hours, only 39 shots!

I’ll add one more, the latest from Wim Wenders. I finally watched Perfect Days recently. It's a pretty special film, so sweet yet mysterious, as with most of Wenders’ work it does so much with so little. The protagonist doesn't talk much. There's no real plot, at first mainly just observing a Tokyo toilet cleaner's daily routines and habits. Little by little more layers are revealed through a few interactions, like with his colleague and when his young niece shows up. Along the way the man’s eye for life's everyday beauty begins to mix with pathos, but the overriding 'vibe' of the film is definitely a certain empathetic equanimity woven into everything.

Stay safe in the storm (in all senses). Hope you enjoy these if you’re hunkering down.

By the way, after my recent bout of flu my guest spot on Takoma Radio has been rescheduled to this Thursday from 7-9pm EST. With host the ‘night nurse’ Madona Tyler LeBlanc we’ll be trading songs and discussing the idea of ‘future music’ in the first hour. In the second hour we’ll talk about how to make such music, with some tracks from my New World Voyage album and I’ll play a few songs live. Hope you’ll tune in!

A Man of a Certain Age

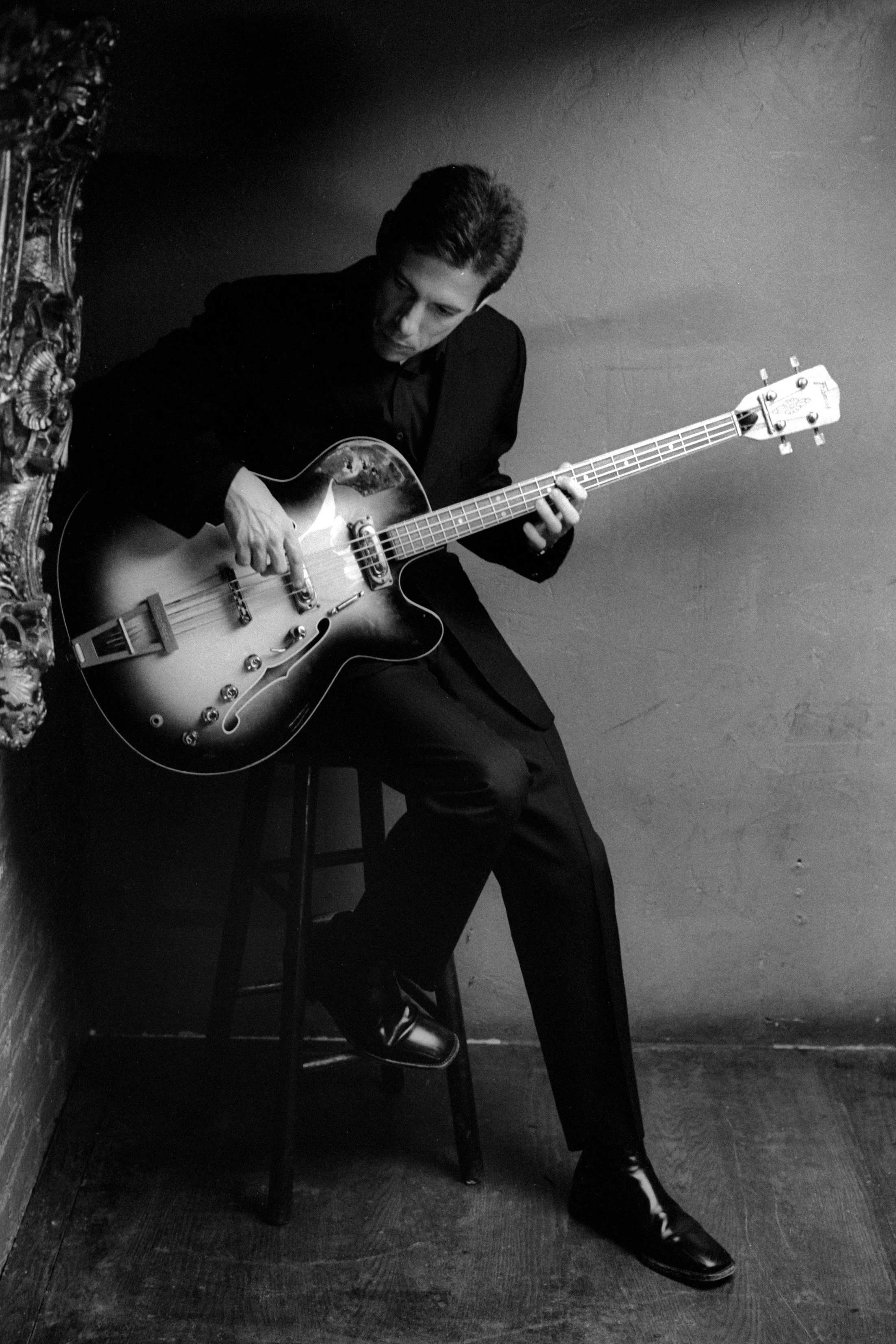

I’ve had a couple of fun shoots for local musicians recently, artist friends I like and admire tremendously. Lynn Veronneau and Ken Avis are the married couple of the outstanding world music (for lack of a better shorthand, sorry guys, I know you read this newsletter) group called Veronneau. I did promo photos for them many years ago, we caught up again last month at DC’s famed Blues Alley in Georgetown. In a twist, Lynn has also been taking my photo workshop lately!

Cory Seznec is another formidable talent and a great guy. I met him in an interesting circular sequence: last summer he reached out about possibly renting our open apartment, he and his family were expats in Paris coming to Takoma Park soon (he ended up renting a different house right across the street from the former childhood home of Takoma Park’s most famed guitar-son John Fahey - not an exaggeration to call Cory a worthy successor to Fahey). My daughter and I ended up in Paris while Cory was still there, so he invited me to play at an open mic on a beautiful canal boat where he was the featured performer. Now we’re both here and he’s taken part in our recent Vocal Takoma pop-up poetry-song events. He just finished recording a suite of songs at Tonal Park studio and wanted some documentation.

So I’ve been staying busy but pressure is building to get a proper job.

One problem is I’ve never really had to do a proper job search. The last time I was worried about it, when photo freelancing started faltering, a photo teaching job fell into my lap and I stayed fifteen years.

I got my first job at age 16 at Rodman’s, a general store near the house where I grew up, because I walked in and applied. In my salad days while playing in bands and going to college I worked as a Vespa courier in DC, in a record store, plus stints as an office temp, a doorman at a new wave nightclub, and a shipping clerk. Almost took the test to be a limo driver but didn’t go through with that. None of those were hard to come by.

Also almost joined the army at 18 and just barely got out of it by the skin of my teeth, that’s a whole other saga.

Briefly moved to London for music. Briefly taught English in Prague.

I finally gave up on bands and music, I just didn’t feel it was ever going to go anywhere. My father taught me photography and it became my marketable skill, my ticket.

For the most part, my working life as a photographer has fallen neatly into a few chunks:

Newspaper photojournalist. I did an unpaid internship for six months because I knew I would kick ass and they would give me a proper job, which I did and which they did. Three to five assignments a day, on hand-rolled Tri-X film, printed in the darkroom on deadline, captions taped to the back of the print as soon as it dried. Later we learned to scan our film for this new thing called Photoshop.

Freelance photographer. Later I shot for a lot of newspapers, like Patuxent Publishing and the Washington Post (thanks Lucian Perkins) in their photo heydays, later the New York Times and various European publications. Weddings, when ‘photojournalistic weddings’ were the new thing. For bands like Thievery Corporation. Made a decent living for over ten years. I developed long-term personal projects like my book The Waiting Room.

Photography teacher. In 2008, I was on a roll with an artist residency in Romania back-to-back with a solo exhibition in Warsaw. But when I got back from Europe the freelance landscape was looking dire and I had a two-year-old kid. Right on cue, an old friend called me about a full-time job opening teaching darkroom photography at a prestigious private school. I had never taught and wasn’t looking for that, but a week later I was working there. Teaching was certainly full of challenges but it was an amazing experience and I kept doing projects and various collabs on the side.

In 2023 I swallowed hard and finally left teaching when we moved to Nairobi, Kenya for my wife’s job. I wasn’t allowed to work there but did some unpaid photo workshops and mentoring in the Kibera slum.

Along the way, after 10-15 years of not touching my guitar, I was invited to join the band Dot Dash. I had to re-learn how to even play guitar, but after a few years I started to have ideas again so I left the band to make my solo album New World Voyage, a concept album about the first humans to leave Earth forever for Mars*. It’s more of an art project, it includes a 40-page booklet using my photos, some NASA photos, and a made-up ‘communications log’ to suggest the fate of my imagined space-faring crew.

*Spoiler: for me, going to a place that has zero of what humans need to survive is a terrible idea. I actually had a fairly lengthy debate about that with the bassist of Sigur Ros when I had the chance to meet them backstage a few years ago. He was of a more swashbuckling mindset about it.

I’m happy to have found my voice, literally/figuratively/creatively, in music. I still don’t expect it to ‘go anywhere’ but I love it and it’s intertwined in all kinds of ways with my other creative endeavors.

So here I am, now A Man of an (Un-)Certain Age, looking for work. What should I be doing? I admit I don’t quite know, feeling a little scattered.

Editorial freelancing isn’t what it used to be, and not sure I would go back to that. I shot a wedding in the Hudson Valley a few years ago and a bat mitzvah more recently for a former colleague’s daughter. Both went well, check my Events page. Guess I still got it. I did build my LinkedIn over many years, we’ll see what that brings now that I actually need it. While I’ll do whatever to keep the bills paid, hope I don’t have to become a barista or something.

With all that said, I’m really only interested in being useful in what I’m more and more calling the ‘fight for our humanity’.

For me, that’s the arts and culture. Arts education, art as community building, supporting artists. And of course doing my own art.

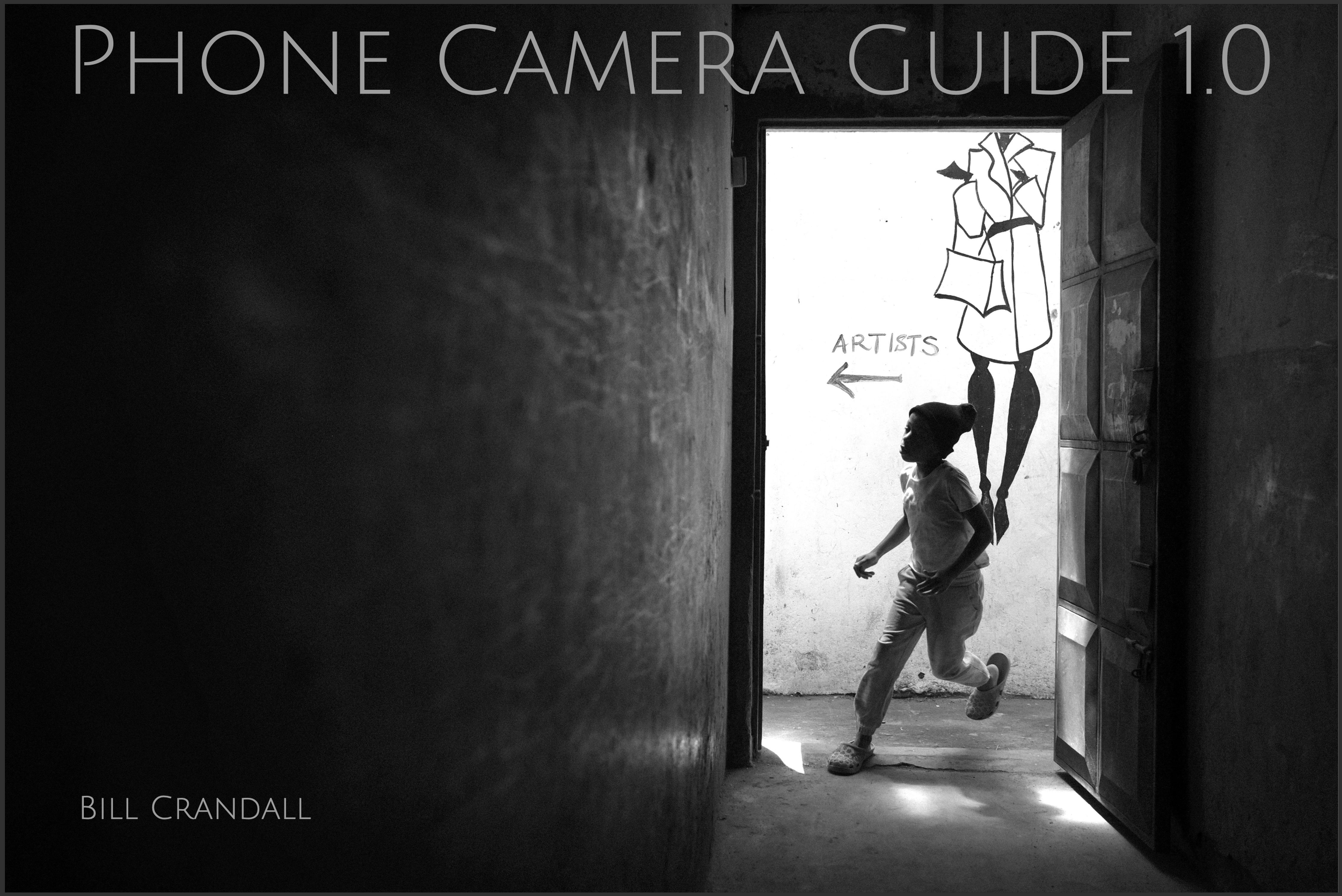

I’m just wrapping up my first in-person photo workshop, called See for Yourself, about developing your own creative vision. What I call authorship. To me that’s the only reason to do photography anymore. Hope to do the next installment soon.

I’m exploring other ways to use my refurbished garage studio as a gathering place, a creative hub.

Musically, I’ve been advocating for what I call ‘future folk’, or ‘folk futurism’. Which, yeah, is sort of what I try to do myself: stories that don’t look back but look forward. Imagining stories of the future so we can get there. I actually worry we have lost the capacity to imagine a positive future.

Stylistically, maybe even more than say blues or jazz or classical, the folk genre can be too trapped in amber, conjuring early Dylan, Woody Guthrie, et al. Or songs with overt, didactic messaging and a bit bound by ‘rules’ - and let’s face it, some often corny tropes. Which is a bit odd since Dylan shattered all the rules. This is not what I have in mind. I think of folk as broadly encompassing, innovative but still simply ‘people’s music’. I’m interested in whoever is doing that in new ways that carry us forward.

A new (future) folk movement, who’s onboard? I’ll be talking about that - and playing a few songs live - on Takoma Radio on January 29th from 7-9pm, co-hosting with the ‘Night Nurse’, Madona Tyler LeBlanc.

I can’t help but feel like the hollowing-out and diminishment of the arts is part of what has brought us to this point. Not that we ever fully win, but maybe art is what has been keeping the wolves of our nature at bay. There’s the joke that the world has gone to shit since David Bowie died but in a general sense there’s something to that. Maybe our art-heroes were in fact protecting us and pointing the way, as I often felt when I was younger. Not sure we really have that now and we see the result.

Where are the new heroes?

Fairytale of Dublin

Dublin’s annual Christmas Eve Busk, to raise money for the Simon homeless charity, has become a pretty amazing tradition. It was started by the venerable Glen Hansard - the former busker who plays a busker in the wonderful film “Once” - and often includes the likes of Bono and Hozier alongside local stalwarts and up-and-comers like Allie Sherlock and The Belgian Blue.

I would say it’s not about the bigger names at all. (In fact I’ve read that Bono was nervous at the challenge of such a stripped-down public singing affair. He and Edge are maybe the stodgiest and most self-conscious of the various performers. Without making this about Bono, love or hate the guy, this year at the end of his appearance he signed off with a nonsensical burst of Polish mimicry. Really strange, not sure what to make of that. Check it out here at the 4:50 mark.)

As The Busk has grown from an impromptu DIY popup to a more polished event over time, what really carries it is the energy, warmth, openness, and spirit of both performers and spectators. Really something to behold.

We need more of this in the fight for our humanity.

I think it was off for a year or two during COVID but in 2021 they somehow did it in St Patrick’s Cathedral and wheeled in a very ill Shane McGowan for what would be his last hurrah.

Have a browse through these videos to get a sense of the shows and some nice behind the scenes vibes. The 2012 and 2015 clips are especially great and worth your time. Keep a lookout for the late Sinead O’Connor, having a grand (if slightly disjointed) time in the throngs of people. What a jolt seeing her!

I've got a feeling

This year's for me and you

So, Happy Christmas

I love you, baby

I can see a better time

When all our dreams come true

Meeting a Photo Hero, Again

Karma takes a strange turn in a reunion of sorts

[Originally published on Medium in summer of 2024. I wanted to get it archived here on my own site, with a few minor updates.]

Something remarkable happened to me not long ago but you need the backstory, I’ll make it short.

In 1998, I attended a documentary photo workshop in Prague as part of my effort to pivot away from newspaper photojournalism, which I had been doing professionally for a few years. I was trying to start over and rebuild on a foundation of personal vision.

Vojta Dukat

During the workshop we had a guest speaker, a Czech photographer named Vojta Dukat.

We were told he was great but little-known, an idiosyncratic, elusive character. We were lucky, he just happened to be in Prague at the time from his home in The Hague, Netherlands, where he had emigrated after the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague. [Note: I’ll save you the time, he doesn’t have a website or much online.]

He came into the classroom, all massive beard and rumpled overcoat, and said to us ‘ok, I will show you my photos’.

He pulled a stack of small work prints from a plastic bag in his coat pocket and spread them haphazardly across the table for us to look at. The printing paper was nothing fancy.

I was floored. Each image was quietly evocative, loaded with old-world mystery, timelessness, and atmosphere. As good as any work I’d ever seen.

This was the direction I craved for my own work. So later that same day I urgently sought him out to get feedback, hoping he’d both affirm my talent and impart to me some secret-sauce wisdom to elevate my game. After all, I was already a ‘professional’ photographer, at a workshop alongside amateurs.

Maybe you can see where this is going.

On that sunny day I found him in a darkened basement pub just steps away from Charles Bridge. After patiently looking through my portfolio, he matter-of-factly dismissed my work — and dismantled my ego — in a matter of minutes.

“I’m sorry, but these photos don’t do anything for me.”

Floored again. I know what you’re thinking. As many friends suggested later, I could ignore his opinion, ‘screw that guy telling you about your art’.

But I had asked, even chased him down - and in that instant I understood completely that he was right. My pictures were a somewhat disjointed hodgepodge of photojournalism outtakes. Something I might offer a photo editor to show how I could handle a range of assignments. It wasn’t that they were bad (they weren’t) but that it simply wasn’t the cohesive, poetic vision I was seeking.

I was in anguish. It wouldn’t be until a bit later that I would recognize the gift he had given me.

I resolved that instead of breaking me it would drive me to play the long game, I would be relentless in setting the bar higher and digging deeper. For the next ten years or so that’s what I did.

Not to be more him but to be more me. I actually started the next day, photographing Prague’s tourist carnival that I would normally flee from.

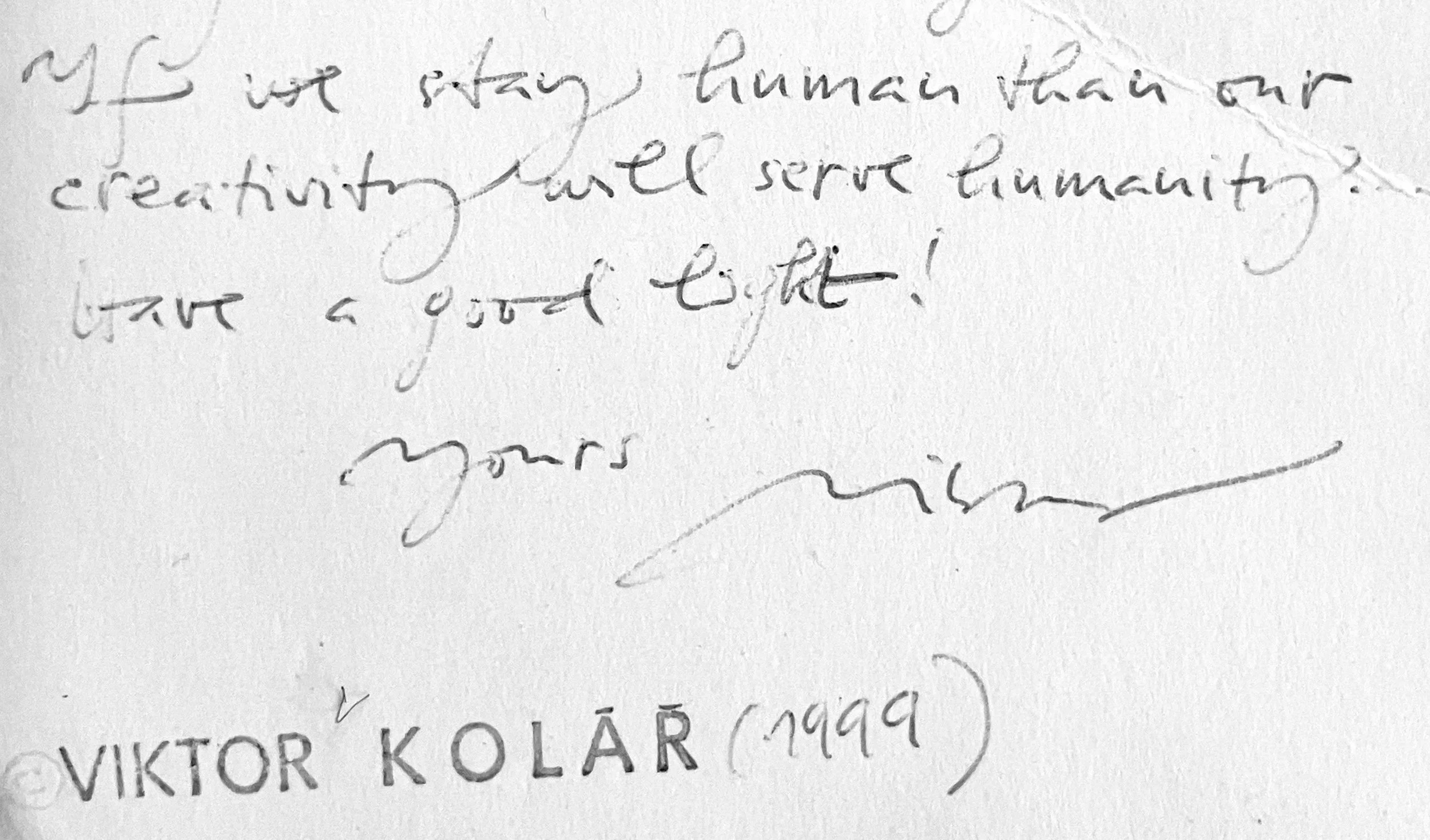

It was a start. Over time I did get not just better and more stylistically coherent photos - what I now call authorship - but a deeper understanding of how your sensibility needs to infuse your work. This is something I learned not just from Vojta but from Viktor Kolar, another amazing Czech photographer I met at the Prague workshop. Viktor to me is maybe the epitome of quiet poetry in photography, and finding that poetry in your own environment (in his case, his industrial hometown of Ostrava).

When I started in photography Josef Koudelka was one of my first inspirations, maybe the best-known Czech photographer. He’s a master of intense, surrealist poetry culled from life. So I owe a lot to the Czechs, and I like them, which is I guess why I talk about them a lot.

Personal vision became the cornerstone of photography and my teaching. You get better when you become more you. The world doesn’t need more cookie-cutter images.

And it started in part with one guy’s simple but brutal honesty, that thankfully I chose to embrace rather than reject. I have had many who inspired me, but he was perhaps the most pivotal.

Um, cool story Bill but why are you telling it now, so many years later?

Because in the summer of 2024 I ran into Vojta by chance in a Dutch train station.

Yep. While visiting in-laws in The Hague, my daughter and I were scrambling through the main train station on our way somewhere, searching frantically for our platform. As we came down a long escalator, out of the corner of my eye I saw a bearded older guy with a walker way down below in the crowd. He was headed for the elevator, three more seconds and he would have been out of sight and gone.

There was no question in my mind. I called his name.

We had just been in Prague and I had talked about Vojta with my old Czech photographer friend, who happens to be good friends with him. He had mentioned Vojta was doing well but had had some kind of bad injury recently. Now here he was, just days later. Crazy.

I wouldn’t say we had a profound conversation and he didn’t particularly remember me. The whole thing was over in a few minutes. I did manage to thank him, briefly recount our previous encounter (I think I stuck with something like ‘you looked at my pictures and it helped me a lot’), and talk about our mutual friend in Prague. I made sure my daughter took a few photos. As his bus pulled up and he hobbled off, he winked and shouted his email address.

I was floored once more (for old times’ sake). I couldn’t get my head around it. What did it mean? Something just came full-circle, what was karma trying to tell me? I have no idea. Maybe it was just a cool coincidence.

Curious about Czech photography? It’s a fascinating and unique creative legacy, with strong roots in surrealism, going back at least a century to the one-armed ‘poet of Prague’ Josef Sudek. Check out the great Fototorst book series, which includes Sudek and the only readily available book of Vojta’s work (my Prague workshop instructor, a well-known US photographer and educator, was equally struck by the work and offered to help him get published but Vojta replied ‘I don’t think you are the one to discover me’). Other photographers I recommend include Josef Koudelka, Karel Cudlin, Tomki Nemec, Bohdan Holomicek, and Viktor Kolar.

A Few Updates

Has it been almost a month since I last posted a newsletter?? I guess I should be used to the swings by now, some weeks the ideas and words flow more than others.

It’s not like there hasn’t been stuff going on. Let me at least play catch up this week.

(This is actually the 2.0 version of this post. Squarespace glitched when I tried to save my first finished draft, lost everything. Which was awesome.)

Music

We managed one more Vocal Takoma popup song/poem circle recently before the weather turned too cold. This time with an actual PA, thanks to a battery generator the city bought for us. It made a huge difference in, you know, people *hearing* us.

David Alberto Fernández

Caleb Wissoker-Cohen

Bill Crandall

Bill Crandall and David Alberto Fernández

Deniz (of Magic Carpet)

Luther Jett

David Camero

Vocal Takoma is not really a group, there’s a small core but it’s more like whoever shows up. And anyone with a song or poem can step up (as they have). My partner-in-art David Alberto Fernandez is using his poet laureate status to try to expand what poetry is and what it can do, especially in this moment we’re in. The idea is putting art where people already are, sort of soapbox-style, helping artists be more seen/heard/vocal. Now we’re moving the model indoors for the winter, figuring out what that might look like.

Some exciting possibilities, stay tuned. I actually believe the revolution starts with stuff like this. See the Czechs' playwright president or the the Singing Revolution in the Baltics.

Photography

I’m part of a group show with the Takoma Artery collective that’s opening at our local community center on Friday. I’ll have 2-3 photos from my Nairobi body of work, one made the lead in our local newspaper.

Freelancing

Since I do have to start making some money asap, I’ve been gearing up for photo freelancing again. Even though I did it for so many years, I don’t really know what freelancing means anymore or what the prospects are. Guess we’ll see. I’m starting a portrait service out of my art-garage studio for starters, and I’ve added some portraits and events photo samples to my site. More soon.

Let me know if you’re looking for:

a new headshot

creative documentation of you, your project/event/band/book, business, etc

photo mentoring or consulting

a quick workshop on getting better photos with your phone, or a more advanced one on being a ‘photo author’

copy photos of your artwork

I offer discounts for the needy. Like fired federal workers, of which there are thousands in these parts. In our small neighborhood alone - one small pocket of one small town right outside DC - a neighbor told me he knew of maybe a dozen families with one or both breadwinners thrown out of work. With mortgages and kids at university.

You can also support me by buying prints from this site for your holiday shopping, take a look here and see what strikes you. With a few clicks you can have high-quality framed photos delivered, as I’m doing for my Takoma Artery show prints.

I guess one common thread in all this is starting where you are. I love where I live, and I’m still happy to be reconnecting and figuring out the path forward since living overseas. I’ve been trying to walk more and I got a Capital Bikeshare membership, the e-bikes help me get around this hilly town. Fit I am not.

Another thread is how in times like these it’s important to attach yourself to groups to leverage your efforts. Don’t always try to go it alone. Even my new garage studio I’m planning to use as a community art-hub.

Power on, people. The horrors are daily and the hope can seem like slim pickings, but focus on those moments when it feels like just maybe things are starting to tip back towards sanity and light, and give it a little flap of the proverbial butterfly’s wing. On other (worse) days, make some art, it helps. Talk to you soon.

Introducing Vocal Takoma

Well that was a fun Sunday.

No newsletter this morning as I was getting ready for a full creative day today. This afternoon was the second session of my six-week in-person photo workshop, See For Yourself. Sorry, I was too locked-in teaching it to take photos, but it’s an awesome group and a great way to inaugurate my garage studio space. Next time I’ll try to take some BTS pics.

This morning before the workshop though was a new collab with some neighbors in Takoma Park. Vocal Takoma (aka VT) is like a pop-up song and poetry circle - or maybe a group busk but not for money - held in active public space. So for starters that meant near our Sunday morning farmers’ market.

VT was conceived by myself and my friend David Alberto Fernandez, who is the new poet laureate of Takoma Park. Yes, we have not only the coolest community radio station around, but a town poet laureate. We wanted a way for artists to come together and to show people art is still kicking. Instead of a venue we take it to where people already are. We want them to see and hear us, and take note that artists are activating, doing something a bit unexpected. Maybe a song/poem/spoken word circle sounds like kumbaya but I have to say while it’s fun there’s a steeliness to it as well.

The idea is a rotating, inclusive ensemble that will have some core participants but change from week to week and even have an open-mic component. We had a lot of interest from other local singers/musicians and poets but due to various conflicts the launch was just three poets - David, Claudia Gary, and Alan Abrams - plus me playing songs. It went very well and it was great to get it going. We did it totally acoustic, no amplification. Soapbox style. Which was a challenge to project but had a certain integrity and intimacy. Still, we’ll hopefully have a battery generator by next time so we can use a little amp, especially those with quieter voices.

While in a way VT is an art action for the times, it’s not directly or overly political. We feel like art doesn’t need to be - and maybe shouldn’t be - political to do its job. Sure, there’s some protest in there as well. Though via songs, poems, and spoken word, it’s just a way of asserting our voices - being Vocal - in support of life, art, our values, and our community. And a model for starting where we are.

A few beautiful moments happened along the way. The shop owner nearby brought out a portrait of her mother, who was a Turkish poet.

David Camero was in jester garb entertaining the kiddos near the spot we were using at the clock tower. We didn’t realize he was also a tremendous local artist and poet, he ended up shifting gears and taking a couple of turns with us.

Come by and check it out some Sunday (we may move to indoor spots as the weather turns). Or, better yet, bring a song or poem of your own.

One song I did was Fortune and Glory, written long ago by an old friend and a band I was in (The Mondays) recorded it. It’s among a batch of such ‘legacy songs’ I’ve been resurrecting, I think it translates well to our moment:

I know a thing or two

Yeah me and you

We just want the truth

And need much more

Than fortune and glory too

I think you can see

What you mean to me

In a world not free

Baby you're worth more

Than fortune and glory too

Right from the start

We knew we had understanding

The hardest part

Is knowing that our day will come

So don't lose heart

New York City is Beautiful

Writing from New York City this weekend. As I’ve been discussing photo ‘authorship’ lately in my posts and my in-person workshop, NY is an interesting case study.

What are you going to shoot there that a) hasn’t been done a thousand times by some of the greatest photographers who ever lived, or b) doesn’t recycle past notions of what the city actually is now?

For years I couldn’t photograph in the city at all. Not one picture. Basically I couldn’t answer those questions for myself, so I was completely paralyzed, short-circuited. I didn’t have a point of view, couldn’t even fathom what that might be.

In the middle chunk of the 20th century there was something called the New York School in photography. It wasn’t a school but sort of a very loose, retroactive grouping of photographers, over several decades, who brought new visual approaches to representing the ever-evolving city. There is some debate over who falls into that ‘school’, and it’s unlikely they thought of themselves as such at the time, but some better-known names include Saul Leiter, Louis Faurer, Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson, William Klein, Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, and Weegee.

Diane Arbus photographing at a beauty pageant, by William Gedney

Photo-authors all. Not describing but interpreting the city, expressing their ideas in personal ways. What united them was a fascination with the city’s complex character and energy and how to convey it in pictures with new visual vocabulary. There was a lot of film noir influence, motion blur, abstraction, layering, graininess, chiaroscuro (contrast of light and dark), and surrealism, combined with a tough-minded humanism.

Louis Faurer

Saul Leiter

Helen Levitt

Places change of course. Like the mid-century Paris of berets, cafes, and baguettes, the New York they knew is gone. It’s a different beast now and requires new visual vocabulary.

So what to do? I remember first visiting then-derelict New York in the early 80s and being somewhat shocked and terrified, but at least it had that CBGBs seedy-but-cool thing. Now it’s more like the terror of banality, too many puffy coats and Disney-fication gone amok. Good luck finding counterculture (or maybe I’m just old), or anything other than shopping or places to otherwise spend your money. At least it’s cleaner.

Some years ago I photographed New York for a European magazine that wanted to show how certain areas were being cleaned up and modernized. Bike lanes, waterfronts, pedestrian zones, that sort of thing. Actually a refreshing take, usually foreign editors go looking for the wacky American extremes.

While shooting I remember thinking, wow, parts of this city are actually QUITE NICE now. Maybe even, dare I say it, beautiful.

Don’t get me wrong, as a series title I don’t mean New York is Beautiful literally. I don’t know, maybe sardonic is the word. Of course New York is not conventionally beautiful and probably never will be. No sane New Yorker, even those who love it, would say it is beautiful. It’s almost anti-beautiful.

But as a contradictory statement, that half serious, half tongue-in-cheek notion finally gave me a starting point. NYIB is actually *two* contrasting sets from the last 10-15 years.

One that I’ve posted about before is experimental. They’re in my print gallery if you want one over your sofa. If you don’t feel like clicking through, here they are:

To me those are a nod to the disorienting, queasy, almost sci-fi dystopia I first experienced. A city out of control, that I could imagine collapsing on itself. I mean I grew up on The Warriors and Escape from New York. But the visual effect is also beautiful. It’s actually a fairly simple analog technique via one of my former students: shooting through cheap kaleidoscope sunglasses I found in a museum gift shop.

To call New York beautiful - or to make it look strangely beautiful - you need something stronger than rose-colored glasses. Maybe kaleidoscope glasses are more up to the job.

The other NYIB set I’ve sat on for a while, I’m showing them here for the first time. It’s sort of the opposite approach: still NY-as-Oz but direct not abstract. Not trying too hard to be something. More like low-key, calm observations that have grown on me.

It’s been helpful to chew on these over time. Even put them aside for a few years to gain some distance. They’re certainly not eye-candy as much as the first set, it’s a very different ‘language’. A couple of bangers maybe but overall leaving room for quieter pics to breathe. Circling back to it now through an authorship lens, they at least feel like mine, that they belong together, and they feel true. Sometimes it takes a while to add up.

Or do they add up? Not sure what they ultimately say about NY, but then again I’m not sure what I ultimately feel about it. Walking around this evening, before my Sunday morning post tomorrow, I had the usual feeling of being simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by the city and the people. We passed through formerly tattered St Marks Place, which I first saw in its grungy punk heyday. It’s spiffed up now, does that make it better or worse?

The city is both impressive and hopeless. Uniquely vibrant and utterly pointless. Fascinating and boring. Energizing and tiring. After a few days I’ve usually had enough.

One could never say everything about New York in photos, that’s for sure. Sort of like the country as a whole, anything you might say is probably both true and false, depending on who you are and how/where/when you look at it.

Both true and false. Sort of like the statement New York is Beautiful.

Saul Leiter seemed to get that with New York you finally give up on sweeping, profound statements. When he got older he was known for mostly semi-abstract color street scenes, content to stay more or less in one neighborhood. In a poignant line in a lovely documentary about Leiter in his final years, he says “if I didn’t do anything more than make my little [photo] book, wouldn’t that have been enough?”.

Minsk, Belarus, Sept 2001

Bringing It Home

My in-person photo workshop starts next weekend, to be held over six Sunday afternoons. As I write this, I’ve got two slots available. Please spread the word. If you or someone you know is interested, I’d love to have you. More info is here.

Came across the above photo while setting up for my workshop. It’s from a 2001 collaboration in Minsk I conceived with Karel Cudlin and the late Uladzimir Parfianok. We seem pretty relaxed, must have been maybe a day or two before our joint exhibit opened *on 9/11*. It was the Czech cultural attache who - soon after the US embassy guy abruptly stopped talking to me and dashed from the gallery - told me ‘planes are hitting buildings’ in the US.

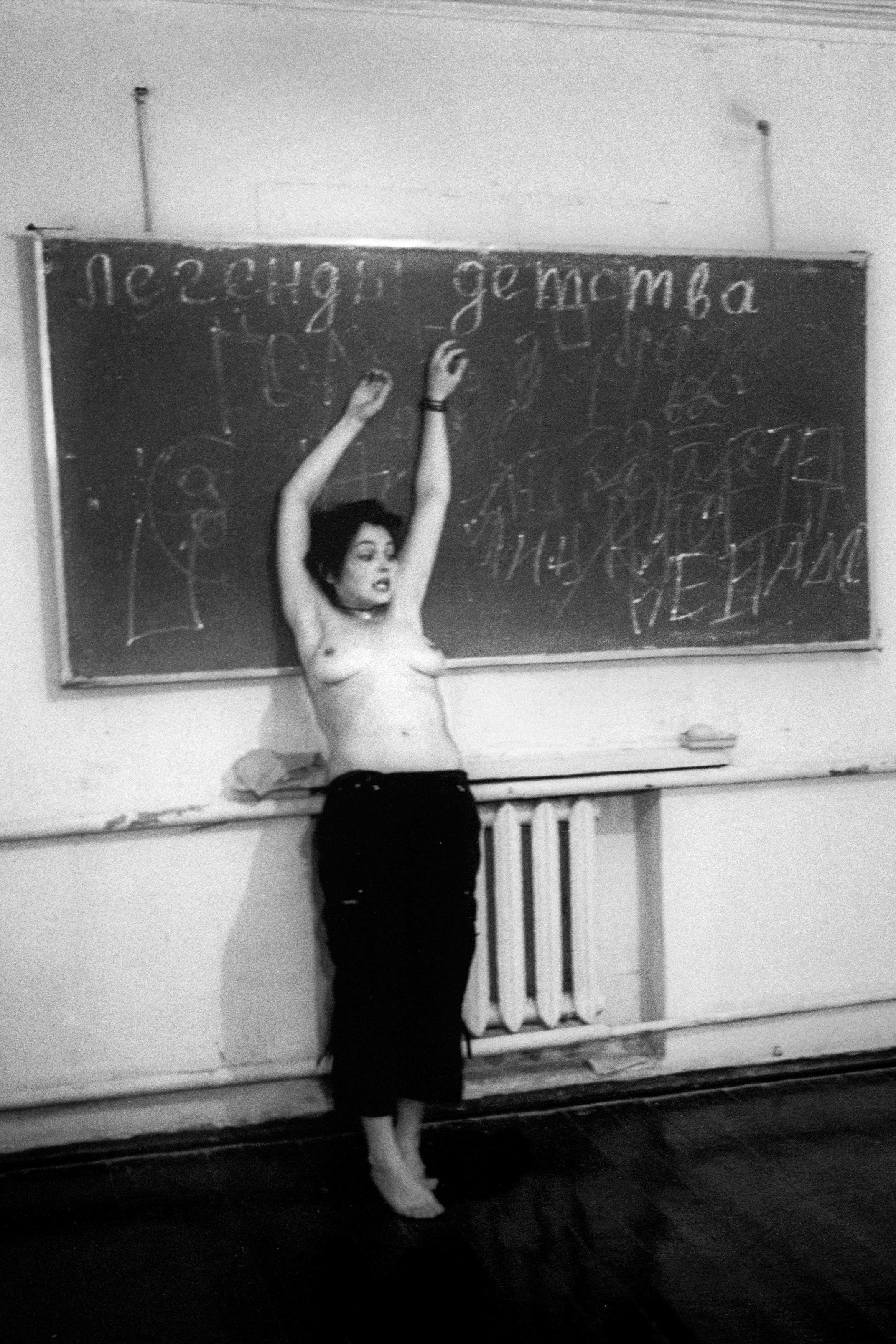

It was a modest endeavor but our goal was more grandiose - establishing the documentary photography tradition in post-Soviet Belarus. The idea of photographers as sensitive, critical, humanistic observers, especially in repressive societies. Documentary photography was not well-known there at the time, due to their history there was state-controlled media photography, a bit of conceptual fine-art photography, and not a lot in-between. We tried to nurture the basic idea that photographers should be out there showing their reality in expressive ways.

And it worked.

Over the next ten years or so a young generation of photographers did emerge. I’m not saying we did that entirely, it could have happened organically anyway, but I know we planted seeds. I’m not sure we could do it today, the repression is much worse there now since the clampdown following the 2020 election. Yes, back in 2001 there was the KGB and bad things could happen to you, but if you weren’t political (as I wasn’t) you could do a lot. I even had sympathetic state media coverage of one of my solo exhibitions there, probably because it was exotic that an American even cared about everyday Belarus.

I don’t think I would (or could) set foot in Belarus these days, sadly. Uladzimir, my late curator friend who organized our shows and collabs, once smiled and told me Belarus was more of a ‘soft’ dictatorship. Certainly much harder now. In a way, working there showed me so much about how repression takes root but how resilience does as well.

Never thought the lessons would feel so pertinent.

In Nairobi I did something similar. I held a photo workshop for young photographers from the huge Kibera slum, who are carrying the torch for telling their own authentic stories both in Kibera and fast-changing Nairobi in general. They are the new wave of Kenyan storytellers, working from the inside, developing their own visual vocabulary. We’ve become friends, I continue to mentor a few of them and I’m sure we’ll keep looking for ways to collaborate.

I’m about to launch a new workshop series here in the US, a compression of my past teaching curriculum. Not that we don’t have plenty of photographers, we certainly do. And a strong tradition of documentary, including the Farm Security Administration photographers that fanned out across the country during the Depression. Still, as I been posting over the last two weeks, I believe what’s needed is a reboot of photography’s purpose, based on personal authorship, in our age of overwhelming image saturation and looming AI.

The photobook reading room is part of my new workshop space

In Belarus, it was about reflecting a country in a moment not just of repression but identity crisis following the end of the Soviet Union. In Nairobi, notoriously difficult to penetrate (for example until not long ago it wasn’t even legal to photograph on the street without a permit), it’s a matter of getting the real stories from a growing African city with an increasingly glossy image but a massive gap in who that growth helps.

In the US it’s a somewhat different task in a different moment. Photography can be about reclaiming our agency, as so many forces are conspiring to smother us, numb us, and detach us from life. Not just the turn toward authoritarianism but more generally consumerism, conformity, and our dependence on screen-life.

Deeply reconnecting with real life and our surroundings - and even our inner selves - could be revolutionary. As I’ve written, photography can help do that. It relies on those connections and it’s a natural remedy for much of what ails us. In a way it’s a question of rediscovering photography’s unique potential but also how to carry it forward in new ways.

Happily, developing those personal connections is also the way to make your pictures better. Making them more you.

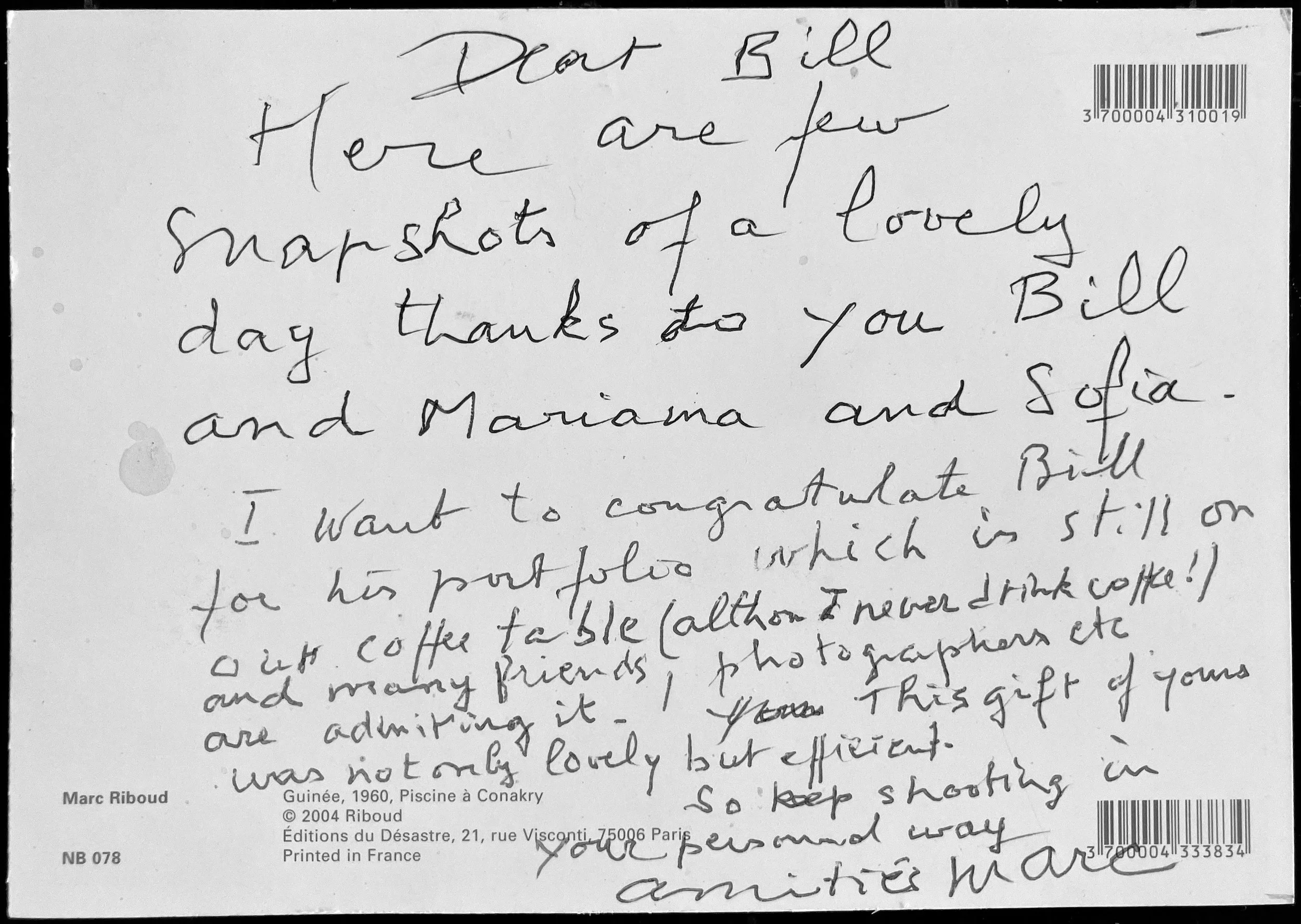

In a way I’m paying it forward for those who helped me do the same. While getting the workshop space ready - and going through a ton of odds and ends since getting back - I found postcards I received long ago from my own photo mentors, encouraging me in my strivings for a more personal vision. One is from the legendary French photographer Marc Riboud in 2007, before he passed away a few years ago. My wife and I had been lucky to become friends with him, this is from after visiting him in Paris with our then-infant daughter:

The other is from the great Czech photographer Viktor Kolar, who I had met in Prague when I was first seeking my own transition from photojournalism to a more personal approach. As always, he put it best.

Maasai near Mt Kilimanjaro (background), southern Kenya.

Authorship notes — I was on a wildlife drive in a national park but I’m a terrible wildlife photographer. Ideas and intentions are important. Mine center on people, our relationship with the landscape, and not wanting to do what others do (like posing the Maasai, which also usually involves paying them). So I jumped when I recognized this as ‘my’ photo.

Notes from the Photo Revolution - More on Authorship

“Revolution? How can photography be a revolutionary act? I thought you said photography sucks!”

Ok, yes, in my last post I led with ‘we don’t need more photographers’ and ‘most photography sucks’.

Which of course was meant to provoke but it’s unfortunately true. As I said, we have way more photography than ever and most (not all) of it is more or less interchangeable. Everyone seem to be lining up to take the same photos as everyone else.

Traffic jam near cheetahs, Amboseli National Park, southern Kenya.

I want to expand more on the idea of photo-authors, whose work is centered on their unique vision and ideas. I believe this is an approach anyone can take, regardless of their experience and skill level, if they want their work to be rewarding and to stand out.

It’s about making your work better by making it more you.

To me, this is the only reason to do serious photography. Otherwise you might consider doing something else.

Maybe revolution can start with resurrection. Resurrecting both photography and ourselves. Hear me out, let’s dig deeper on a few levels. How do we actually become a photo-author?

First, we need to remind ourselves what photography requires of us.

Photography begins not with cameras but with observation. An elevated state of keen, conscious noticing, driven by curiosity.

In general, most people don’t really see, or even bother to look except at the obvious. But while paying quality attention is a fading art, it’s something anyone can train themselves to do. First you notice things (like an interesting tree or person), then less tangible things like the quality and direction of light. Then you start seeing visual relationships between things, and between things and what’s around them, and that’s when it gets good.

Once you start doing this it’s hard to stop. What do you notice that others don’t?

Underpass, Minsk, Belarus.

Authorship notes — When you see ‘your’ photo in the visual relationships and the moment, it can require courage to pull it off. Be prepared to ask forgiveness not permission.

These days, one of the main problems with noticing in the Age of Screens is our increasing detachment from what is actually around us. I think this is a major aspect that is not talked about enough in the context of creativity. In my last few years of teaching photography I saw a significant decline in my young students’ interest in their surroundings, their basic visual curiosity. Especially after COVID.

To a degree they’ve swapped it for what’s in the little box in their hand. Don’t scoff, we have too.

The way devices put the world in our hand is miraculous — and an existential problem for photography, which has always thrived on celebration of the everyday. How can the everyday compete with the bling of anything-anytime? Who cares about the slice of life in front of me when the whole pie is in my hand?

We are getting re-wired. Fight it.

After observation comes engagement.

What do you do with what you see? This is where your visual vocabulary comes into play. Playing with light, composition, angle, moment, etc.

But don’t stop there. Photography is not just pictures. It’s about who we are. It’s directly tied to our compassion, humility, openness, courage, curiosity, experience, and worldview.

Photography asks for rigorous engagement with real life. Photographers have to get out there, and are supposed to be both sensitive and tough observers/interpreters of the world and the human condition. Beauty-seekers, truth-tellers, story-tellers, like any artist.

Collective farm worker, Belarus.

Authorship notes — This was born of failure mixed with mindfulness and courage. We asked to photograph at a Soviet-style farm, while we were waiting to be refused by the director, this guy was standing behind me. I didn’t ask, I just took it quickly from very close range. He wasn’t bothered and I went home with a photo after all. At my exhibition in Minsk, a young Belarusian guy said it captured “not just this man but my country in this man”. Right before another woman told me I didn’t have a clue about Belarus. Win some lose some.

Pretty only goes so far. To really elevate your work, you will need to challenge yourself on deeper levels.

If we can agree photography is a tool for reconnection with the world and life, I’d say that’s the first thing that needs resurrecting. What’s next?

Photography is a tool for reconnecting with ourselves.

Just as we’ve become detached from our surroundings, we’ve become detached from our inner selves. To become an effective visual author, it’s critical to re-establish those threads to our imaginings, tastes, ideas, dreams, instincts, memories, wishes, even our pain. Then try to channel that into your work.

Notice what you are drawn to, and not drawn to. Experiment. Trust your instincts. But also challenge your instincts.

Yep, sorry, you might need better instincts. I did.

If we snap to a screen any time we have a spare moment, we are denying ourselves those moments of personal headspace — including boredom and its creative benefits — that allow our own thoughts to percolate instead of always fielding the barrage of incoming information.

Just as anyone can learn better noticing of their surroundings, anyone can train themselves in the habit of tuning inward — noticing and nurturing their inner landscape instead of relentless external distraction and a growing aversion to our authentic selves.

In other words, photography requires mindfulness. Photography IS mindfulness.

I made a transition to personal authorship after I had been a professional photojournalist for about six years. I had some un-learning to do and some reconnecting with my original inspirations and impulses. I sought out feedback from a very select few, even if that feedback was painful at times. I shed my ego in order to rebuild from scratch. It took time, it’s a long game.

Parade rehearsal, Minsk, Belarus.

Authorship notes — I was surrounded by at least ten other photographers who didn’t react to this. Maybe they did see it but it wasn’t ‘their’ photo. It was definitely mine, I ran toward it.

But something interesting happened. I had been working regularly and doing fine, but I felt like I was hitting the wall and not advancing. Soon after I consciously planted my flag on my own way of doing things, I began to become more successful.

I started getting more exhibitions, awards, and opportunities like artist talks. I got a photo teaching job with no teaching experience. I made a photo book on Belarus that won an award and opened more doors. People do look at you differently when you have a good book.

Who makes books? Authors, visual or otherwise.

If there is to be a photo revolution — one that can contribute to photography’s relevance as an art form in the age of AI — it will come from photo authors. Those who dig deeper to inspire and surprise us with work that is more personal, authentic, unique, and powerfully human.

Anyone can do it.

Your current experience level is not important. If you are just starting, you are more open to ideas and the tech learning curve is not steep anymore anyway. You might be better off, often professional photographers are more set in their ways.

Your choice of camera is not important, any camera is fine if you’re comfortable with it.

There are basic building blocks to consider in pursuit of authorship:

Developing your ideas

Making your work personal

Reconnecting with the world, your inner self, and other people

Being relentless, willing to push yourself

Not letting ego get in the way

Recognizing ‘your’ photos

Not making photos that you think others want to see. That’s the kiss of mediocrity. Bend people to your vision.

Your attitude toward your subject (as Miles Davis said, “It’s not the note, it’s the attitude of the motherf**ker playing the note”)

We’ve seen it all. What do YOU want to show us and how? How is it different from what we expect to see? How does it resonate with your passions and point of view?

Only you can figure that out.

Can photography change the world? I don’t know. Probably not.

What do you think?

People talk about how it creates awareness. I don’t think the problem is that we’re not aware. I think we need inspiration.

Mystery, magic, stories, and surprises in photography or any art form. To be swept up in a well-honed vision of life and the world, to help us believe in ourselves and the future.

Photography can change you, start there.

You don’t have to be or aspire to be a ‘real’ photographer. Certainly not a ‘professional’, I don’t really know what that means anymore.

What the world calls for is energized, creative, empathetic observers reclaiming our agency and connection.

I know photography has definitely changed me — years of looking at it, doing it, trying to do it better, teaching it. I am a different (I would say better) person because of photography, and a better photographer as a result. It has become my way of understanding the world and trying to put that understanding into visual form. I’ve seen it change my students.

The deeper you go, the more it changes you.

If you’re doing it well, it might just change others as well.

Pretty revolutionary.

More info on my upcoming photo workshop here.

2007 (If you’ve been to Prague, you can guess what they’re looking at. How many phone cameras would there be in the same scene today?)

We Don't Need More Photographers

[Author’s note: This week is part 1 (part 2 next week) of what I would call my photo manifesto. I’ve published a version of the piece below on Medium and Substack earlier in the year but not in this space yet.

It coincides with the launch of my upcoming photo workshop - a six-week, in-person, small-group format called See For Yourself - on October 26 in Takoma Park. It’s a kind of distillation of my 15-year teaching career, it resembles an indie version of my advanced Photo Seminar class at Maret. If you’re interested, a PDF with more info is here. Act fast, I’ve already got a few people in the pipeline and space is limited to six participants. The focus is on developing a personal approach and, more broadly, reclaiming our agency and vibrancy through photography. In brief, as I put in the overview:

Photography is energetic engagement with the world, other people, and ourselves. The quality of the photos reflects the quality of that engagement, and the ability to translate that engagement visually.

Photography is not just pictures, it’s a stance: curiosity, empathy, mindfulness, a worldview. That's a revolutionary stance.

All experience levels welcome!

I’d been wrestling with the idea of online courses for a while, finally I decided IRL is the way. So for now that’s what I’m doing. I have a new boho studio/meeting/music/photo library space that I’m excited to inaugurate.]

“Most photography today sucks. We are drowning in pictures, too many of them formulaic, banal, or mediocre. We have enough, we should just stop. Why bother?”

Over my 15-year photo teaching career, I would sometimes start my classes for the year with statements like these. They were meant to provoke my new students and get their attention.

Wait, our photo teacher thinks photography sucks??

Well, consider some of the greats of 20th century photography, just to name a few: Gordon Parks, Josef Koudelka, Diane Arbus, Daido Moriyama, Ansel Adams, Mary Ellen Mark. They had very different strengths, skill sets, and circumstances but each had a powerful, singular voice. It is quite easy to identify their photos just by looking at them. That’s what made them great.

Today you’d be forgiven for thinking that much of what you see out there (usually online) was taken by the same person. Pretty perhaps, maybe even visually interesting, but too often not compelling or distinctive. Weak sauce.

Of course there is powerful and sensitive imagery being made on a regular basis by talented photographers, but you need to dig for it. There are young photographers across Africa carrying the torch. Finding new visual vocabularies and telling their own stories. I know because I met a few of them at a workshop I gave in Nairobi.

But the firehose of images made every day is drowning out the good stuff, making it harder to find — and even slowly chipping away at the very notion of ‘good stuff’. If it’s true that everyone’s a photographer now, maybe it means no one is. I hope it’s not controversial that today’s ease and sheer quantity of image-making has been democratizing photography but not necessarily making it better.

Of course, from a DIY standpoint this democratization is a dream come true and traditional gatekeepers are an elitist vestige of the past to be vanquished. So that gets complicated, and this is not a piece advocating for gatekeepers.

Still, I do believe my provocative statements, to a degree, with plenty of caveats. Of course anyone should do what brings them joy, in any way they like. There are countless ways and reasons to make pictures. Doing it just for fun is fine, in fact I encourage people to do photography for themselves. Any camera will do. Sometimes so-called professional photography is the worst.

As a practice, photography has become much less of an artisanal craft but is still a tremendous mindfulness exercise. Being attentive to beauty, other people, and our surroundings has its rewards for our well-being. Those are good reasons right there.

Yet “why bother?” was a question I posed to my students. Why strive and struggle to make images just like those that have been made by others, over and over, for decades, so they keep piling up?

We don’t need more ‘photographers’.

Meaning those who want to be famous (does anyone really believe this?) or rich (extremely unlikely), who are obsessed with equipment or technique (I assure you it’s not about cameras or f-stops).

What we need are photo-authors.

Those able, even determined, to show us their vision and ideas in new and surprising ways.

Those with the courage — because courage is required — to infuse their images with their sensibility. Their unique point of view, personality, stories, and ideas. This means a continuous deep dive into yourself in parallel with figuring out how to put that into your work.

As the great Czech photographer Viktor Kolar once told me, “if you want to elevate your photography to something more spiritual, develop your sensibility and learn how to make it visual.”

It’s really not about who can make the ‘best’ photos anymore. Those days are over. To use a music metaphor, imagine one of those TV singing contests like American Idol. Think about the panel of judges deciding who hit their high notes the best and checked certain boxes. Usually they sound mostly alike and will not have much impact on the listener.

Too often, that’s photography.

Now imagine, say, a young, unknown Bob Dylan taking the stage on American Idol. His lyrics, voice, guitar playing, and demeanor utterly idiosyncratic, unconventional, even contrary to the notion of ‘good’. Doing things completely on his own terms. He would probably get yanked off-stage. Yet he became one of the most celebrated musical poets of all time, with vast impact and influence across decades and genres.

Which one do you want to be?

Don’t worry, you don’t have to call yourself a ‘photo-author’ out loud, it does sound a bit pretentious. Not the kind of thing one says. Use ‘photographer’ but think of yourself as an author. It can be your undercover identity as a art-spy.

Being an author of course requires having ideas, which for many people is a scary prospect: “What if I don’t, or what if they’re no good??” Rest assured, you don’t have to know what your ideas are in advance. But you can still commit to developing them as a vital part of your process, and they will come.

I didn’t used to have ideas. Now I can’t keep up with them.

It’s a transformative process that asks more of you than simply shooting a lot and hoping to get some ‘good ones’ to show off. Don’t stop there, as many do. The main reason photographers don’t advance beyond technical competence is failure to wrestle with their ideas.

Photography is a kind of return on investment — in yourself.

Often ego gets in the way just as photography gets hard. People would often prefer to convince themselves their pictures are good enough as-is, rather than do the difficult — even painful — personal and creative work to make them next-level better.

WHY are you photographing, what are your goals, intentions, and ideas? This comes from your critical thinking, your observations, your instincts, your dreams. What books you’re reading, films you’re watching, music you’re listening to.

HOW do you make your ideas as visually effective as possible? This includes basic technique, but also finding your own strategies, visual approaches, and experimentation. How you interact with people and your surroundings. These also take courage, the world right now is not an easy or safe place for critical observers.

If all of this seems daunting, keep in mind that even my youngest photo students — 14-15 year-olds who would get kind of wide-eyed when I said these sorts of things — were able to understand the quest, and forge the beginnings of a personal vision. Sometimes in just a few months they began to make and recognize ‘their’ images. Sometimes right away. Usually not consistently or with technical polish. But their best images were mysterious, evocative, sensitive, curious, poetic, raw, compassionate, suggestive. And this was darkroom photography, where you have to do twenty things right even to make a bad picture.

Which are all great reasons to bother. I could look at my students’ best work all day long (which of course is what I did). These were not sunsets, kittens in a basket, or overworked Photoshop contrivances (or, god help us, AI fabrications).

We don’t need more eye candy or sentimentality in the world. As Viktor Kolar also liked to say, sentimentality won’t save us.

If you want to know how to make your work better, make it more personal.

In a world where truth, intelligence, decency, and hope are under siege, I would argue we need all of the arts to assert a new humanism, a word which has fallen out of fashion over the years. A newly confident, savvy humanism springing from beauty, poetry, and solidarity. But not soft, it’s the new punk-rock stance. Ready for a street fight with the alternative.

The unique ability of photography to reflect our world in profound ways can be reclaimed by skilled and committed photo-authors — who can also help reclaim our zeitgeist from cynicism, despair, and pervasive dark trends. And in the process maybe even help us imagine a better future.

Is that all a bit much? Ok, maybe. But hasn’t the world dimmed a bit since smartphones/cameras and selfie culture took over, and the stream of mediocre images became a barrage?

Ok, or since David Bowie died. Coincidence?

I admit my beard game has slipped since someone made this of me a couple months ago.

New World Voyage

After playing in parks and open mics abroad over the summer to get fit, I’m back in the New World and excited to report I have a proper gig coming up. Am I ready to play for two hours? (Just flew in from Nairobi and boy are my arms tired, ba-da-boom-crash.) Guess we’ll find out!

‘Hey Bill, I don’t really know what kind of music you play.’ Good question, it doesn’t fit a neat genre. All original, I call it future-folk. I mean it’s indie rock of sorts played on acoustic guitar, not much actual folk in there. But they are songs that strive to reflect the times, carry us forward, and help imagine the future.

My musical ambitions are way different than when I was younger: now it’s not fame but the doing. Art at the community level. IRL. An element of storytelling. An element of art-warrioring in our current moment. The way making music makes me feel as a whole body-mind-spirit endeavor. And of course any shows should be nice and early, especially on a weeknight.

It’s also about resistance. As I’m reading right now in the book “How to Fall in Love with the Future”, artists must be part of imagining a positive future and helping us get there. I just read a part early on about a 95-year-old woman who was part of the French Resistance. She said her comrades had one thing in common:

“They were all optimists”.

If you’re in the area, I hope you’ll join me, I’m hoping to help activate Takoma Bev Co as a low-key music hub, in a 60s coffeehouse spirit. It’s perfect for it.

by Geertjan Cornelissen

My life has always been a push-and-pull between photography and making music. I’ve played in bands my whole life but solo-Bill started with my 2016 concept album New World Voyage, about the first people to leave Earth forever for Mars.

Spoiler: a terrible idea (Mars, not the album).

One song imagines the morning/mourning of departure, the crew getting their heads around the enormity of what they’re doing, of the whole human enterprise coming to this point:

I send my soul

Amended heart

I know there'll be a place for us

To start anew, I couldn't without you

From the shore

Through a forest of fallen gods

Is this the only path for us?

A way to pass through, on our way to You?

It’s a music album but also an art project. There’s a 40-page PDF booklet about their journey, using my photos, NASA photos, drawings by my daughter, and a ‘communications log’ suggesting more about their fate.

https://billcrandall.bandcamp.com/album/new-world-voyage

WAMU wrote about it at the time:

http://bandwidth.wamu.org/space-isnt-the-place-mistochord-scores-a-fraught-migration-to-mars/

I wondered who would do such a thing, leave Earth? I imagined one crew member as a formerly trafficked woman trying to get as far from her demons as possible:

Feeling a landslide

Bartered and sold

Once in a nighttime

Waits to be told

Wants to love again

To take control

Wants to break this ordinary hold

My thesis was the crew would be semi-deranged by the time they arrived, hallucinating and speaking in gibberish. Dealing with injuries or deaths or pregnancies on their one-way, months-long journey. But the biggest challenges being psychological as they grow increasingly numb and lose their shit:

Hold my face

Stood and found a laden dog

Cool eyes wait

Dead he said and walls that talk

I don’t know how much I care

I don’t know how much I can understand

One of my self-imposed concept parameters (ok, that we didn’t fully adhere to) was that it should be conceivable that the music you hear was made aboard the ship. Meaning they may have smuggled in a guitar or a mini-keyboard but there wouldn’t be, say, a drum kit. So for example any beats should sound like they were made by the ship itself, the mechanized environment.

We used public-domain recordings by NASA Voyager as a ‘bed’ to many tracks, so you feel like you’re onboard. Yes, I know, there’s no sound in space. The best way I can explain it is that as it hurtled past the planets, Voyager recorded space frequencies, the solar winds, that could be translated into audio.

Interestingly, different planets have different audio character. Mars sounds more sinister than Earth.

Then the big ‘now what?’ moment - how in the hell to strip away all those studio layers to play the songs live as solo acoustic, something I had little experience with. That’s been a learning curve, and still is.

The songs written since have been more ‘meanwhile back on Earth’, more grounded in love and solidarity in changing times. The underlying climate theme is hand-in-hand with creeping fascism:

Come and take me out of here

Come and take me slow

We’ll take our time as voices near the window

Cranes collapse and faults collide

Small boats are not safe

We’ll take the road at mud tide as you say

Lovers separated by war in Bosnia, as the waters rise:

Great green river cuts through the town

On its way forward

The past rushed over, submerged

You know I can’t quite find you

My breath is still inside you

A kind of storm

My newest song takes a more warrior stance:

Bring on another time another day

It may not soothe me

Open up my eyes to find a way

It don’t confuse me

Going in with eyes wide open

Gonna blow this thing wide open

My solo ‘career’ (cough) is now in roughly year ten, still gets me out of bed in the morning. Making any art is part being in the present and part creating the future. Standing up for the kind of world I want.

Yeah, I do use the word imagine a lot.

As bell hooks said, “What we cannot imagine cannot come into being”.

With my mom

DC Shirts - More Colors and Sizes

Back in occupied DC. Well, just over the line in Maryland, I haven’t really ventured into the city proper yet. On social media I did read about a few ICE sightings and police checkpoints nearby but it hasn’t hit me in the face yet. Seems the National Guard is mostly on mulch duty closer to downtown.

Last week I posted my new DC t-shirt design, an homage to ACDC borrowing their logo font and lightning bolt. I’ve just added two new darker colors - ‘vintage black’ (basically dark gray) and dark olive - and a 3XL size, check out the new lineup.

https://bill-crandall.squarespace.com/store/dcaf-unisex-t-shirt-new-colors

I picked up my sample shirt at the post office, did a quick change in a cafe restroom, and stepped out like Superman from a phone booth. In the first few minutes I got ‘hey, I like the shirt!’ a couple times.

I can vouch for the quality. It’s comfortable material, a nice slim/tailored fit. I’m six-two with my shoes on, 190 lbs, and a large fits but with not much extra room.

Got my first review!

“It looks really good. We were really happy with the color choices. Given the somber times, neutral and muted seems appropriate.

My hubby is the god of T-shirts, wears nothing but, he was super psyched to get this T-shirt as was I.

I like your logo in the shirt collar, nice touch.”

Via Signal, how apropos.

Give Me a Vote sculpture, Shaw

Free DC

I was at an expat lunch at someone’s house the other day here in Nairobi. As it turned out, several people there had various ties to the Washington DC area. I was saying that when I was back last time in April-May, I was expecting a dystopia but had actually enjoyed it despite everything.

“Well, you might get your dystopia now,” one woman said. Indeed.

I won’t do a deep dive into what’s going on. You know what’s going on. How I feel about it won’t shock anyone, nor vary much from how you feel. No need for me to go on and on.